In recent years, I’ve noticed a growing phenomenon among American English speakers. People with otherwise “standard” accents exhibit a “non-standard” pronunciation of words like price, right, and kite. To use right as an example, this results in pronunciations which sound to listeners like “rate,” “royt,” or “ruh-eet.” To put that into impressionistic terms, the diphthong seems to become “tighter.”

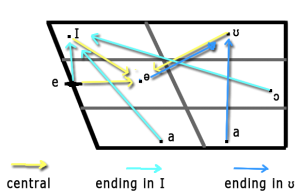

This quirk is due to what might be termed the price-prize split. In many accents, there is a difference between the ay sound in “price,” “right,” and “kite,” and the /ay/ sound in “prize,” “ride,” and “flies.” Before a voiceless consonant, the /ay/ vowel is shorter in duration and sometimes different in quality (e.g. Canadian prize–IPA praɪz–contrasts with Canadian price–IPA prʌɪs).*

(I realize that, contrary to the title of this post, this isn’t a matter of “rhyme.” But I dunno … “Price and Prize Aren’t Assonant” doesn’t pack the same punch. )

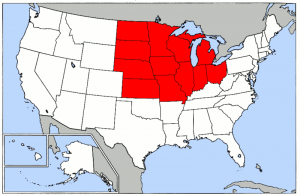

The price-prize split is most commonly referenced as a feature of Canadian Accents, part of the phenomenon of Canadian raising. But it’s heard in many other accents as well:

—In Scottish English, prize = IPA praez while price = IPA prʌis

–In some Newcastle (Geordie) accents, prize = IPA praɪz while price = IPA prɛɪs (See citation 1)

–In some contemporary Dublin accents, prize = IPA prɑɪz while price = IPA præɪs (see citation 2)

I’ve noted similar, less-discussed distinctions. For example, It’s apparent to me that some New Yorkers pronounce “right” and “ride” differently: where the former is similar to other American accents, the latter diphththong has a back onglide (i.e. IPA rɑɪd, making it sound like “royd” to outsiders).

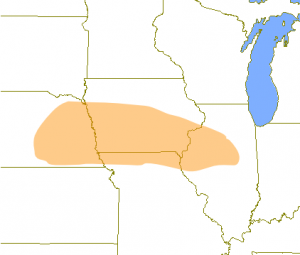

In fact, it seems that various types of price-prize distinctions have become very widespread in the US. Perhaps the most well-observed of these splits is found in parts of the American South, where price is pronounced as it is in General American English, while prize is “prahz” (IPA pra:z).

But I’ve heard similar splits in parts of New Jersey, various areas of the Northern US, California and the West. Indeed, I myself make a slight distinction between the two words (probably along the lines of IPA praɪz vs. prɐɪz, for you phonetics hounds out there).

A related observation is that most English speakers pronounce “price” with a much “faster” diphthong that the diphthong in “prize.” If you’re a native English speaker, give it a whirl: say the word “right” then the word “ride.” You’ll notice the latter has a longer, more drawn out quality than the former. It’s logical that, when pronouncing a diphthong more rapidly, the actual distance between the two vowels might shorten, yielding a different pronunciation.**

What I wonder, though, is why some accents make such a large distinction between the two, whereas other don’t. For example, why do areas in the mid-Atlantic (i.e. Philadelphia, Baltimore, etc.) exhibit such a large divide between prize and price (often ɑɪ vs. əɪ), while New Yorkers only make a slight distinction (perhaps ɑɪ vs. aɪ)?

Any other PRICE-PRIZE splits worth mentioning?

*Phonetics novices may notice I’m using a lot of the International Phonetic Alphabet in this post. I normally try to use accompanying “laymen’s transcriptions,” but since I’m discussing minute distinctions here, I found it difficult. You may want to consult my IPA cheat sheet. Or, if you have more time, the International Phonetic Alphabet tutorial I created some months back.

**Articulatory phoneticians would have a lot more to say about this. I’m speaking very generally.

Citation 1: Watt, Dominic & Lesley Milroy. 1999. Patterns of variation and change in three Newcastle vowels: Is this dialect levelling? In Foulkes & Docherty (eds.), 25–46.

Citation 2: Hickey, Raymond. 2000. Dissociation as a form of language change. In European Journal of English Studies (4:3), 2000, 303-15.