[Ed. note: An earlier version of this post had an embedded sound clip of Philip Shaw reading a letter by Richard III in a historically accurate accent. Unfortunately, I’ve had a few embedding issues since updating to the latest version of WordPress, so for now, click on the link four paragraphs below this one to hear the relevant interview.

[Ed. note: An earlier version of this post had an embedded sound clip of Philip Shaw reading a letter by Richard III in a historically accurate accent. Unfortunately, I’ve had a few embedding issues since updating to the latest version of WordPress, so for now, click on the link four paragraphs below this one to hear the relevant interview.

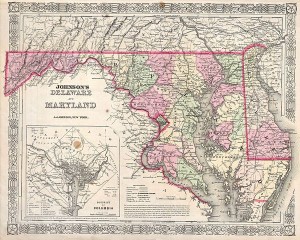

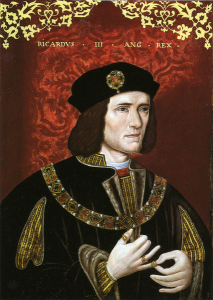

Experts confirmed this week that a body found under a Leicester parking lot/car park belongs to Richard III. It’s an exciting discovery and a crucial step in establishing the differences between the historical king and Shakespeare’s less-than-flattering portrait.

Accent enthusiasts may be puzzled, however, by a series of news stories about RIII’s “Brummie Accent.” Most quote University of Leicester professor Philip Shaw, who has this to say on the matter:

Unlike today, individuals were more likely to spell words in ways that reflected their local dialect. Therefore, by looking at Richard’s writing, I was able to pinpoint spellings that may provide some clues to his accent.

To be clear, though, Richard III did not have anything remotely resembling a contemporary Brummie accent. Nor is Shaw suggesting this. Listen to this wonderful interview, in which he gives us an idea of how the king would have spoken.

Needless to say, this is hardly classic “Brummie,” as headlines suggest. We’re talking about the earliest stages of the Great Vowel Shift, when the language would have sounded foreign to most contemporary ears.

Whatever marked a West Midlands accent at the time would not necessarily have been what marks that accent now. Brummie today is noted for its lack of several distinctions common in England’s South (the FOOT-STRUT and TRAP-BATH splits) and a number of vowels which somewhat resemble strong, vernacular Cockney (i.e. the long trajectory of the diphthongs in KITE, GOAT, and FACE). It’s unlikely any of these features would have been sociolinguistic markers in the 15th-Century.

We are accustomed to seeing films about Henry VIII or Richard III in which everyone speaks the Queen’s English, but it bears repeating that this is a dramatic convention divorced from reality. It is doubtful contemporary Standard English-speaking time-travellers would be able to easily understand their own language until at least Shakespeare’s time. So needless to say, “Brummie” means something very different here!