Harry Reid

I first heard the word ‘dialect’ within a bizarre context. It was the 1980s, and some adult (whose identity I forget) used it as a euphemism for African American English*. It was something along the lines of, “He speaks dialect, so I had a hard time understanding him.” ‘Dialect’ needed no qualifier or article here; it was a given that this single word referred to the speech of an entire ethnicity.

This rather icky reinterpretation of the term was revived by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid during the 2008 presidential campaign, via this cringe-inducing anecdote (here recounted by CBS News):

[Reid] was wowed by Obama’s oratorical gifts and believed that the country was ready to embrace a black presidential candidate, especially one such as Obama — a ‘light-skinned’ African American ‘with no Negro dialect, unless he wanted to have one,’ as he said privately.

Although Reid awkwardly specifies the type of dialect he is talking about, I doubt he would have mentioned a candidate’s ‘Tennessee dialect’ or ‘New York dialect’ (he probably would have used ‘accent’). The word apparently became reserved for African Americans at some point in twentieth century America. (That using the word ‘negro’ is ridiculous in this day and age should go without saying).

And this is hardly the only example of ‘dialect’ being misused (or in Reid’s case, being used correctly but cluelessly). I’d also cite an ill-informed adjunct professor of mine who once remarked, “I guess you could say an ‘accent’ is the way a native speaker says something, while a ‘dialect’ is the way a non-native speaker says something.” Ouch. Again, there seems to be a vague understanding of what a dialect is, and yet the speaker would be hard pressed to actually define it.

‘Dialect,’ I would argue, is not a household word in America. As these anecdotes suggest, it’s often misused and misunderstood. ‘Accent’ on the other hand, seems to cause no confusion, and has emerged as the more popular of the two words. This is even true of Americans’ search habits: Google Adwords’ Keyword Tool estimates about 33,100 local monthly searches for ‘British dialect,’ but a more robust 60,500 local monthly searches for ‘British accent.’

And yet you could argue that ‘accent’ is the more vague and confusing of the two terms. ‘Dialect’ describes the whole package that comes along with regional or sociolinguistic variation in a language: grammar, phonology, and lexicon. ‘Accent,’ on the other hand, really only refers to our pronunciation.

So it’s odd that of these two words, the one with the largest number of unrelated meanings won out. ‘Accent’ can be used in a number of ways in linguistics, and a whole host of other ways besides, whether we’re talking about the ‘accent’ of an interior decorating scheme, an ‘accent’ in a piece of music, or the Hyundai Accent. Type ‘dialect’ into Google, and 9 out the first 10 search results relate to linguistics. For ‘accent,’ this numbers only 5 out of 10.

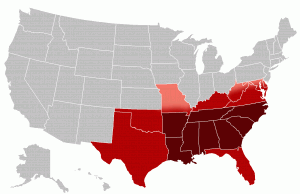

To repeat something I’ve mentioned before, it’s possible America’s lack of ‘traditional dialects’ has prevented the word from taking hold. In the UK, there are dialects that sound to outsiders like separate languages (although many of them are receding), retaining features that hark back to the very dawn of the language. Here in America, a Pennsylvanian might say ‘The car needs washed’ where I would say ‘The car needs to be washed,’ but it is only in a select number of dialects (Appalachian English and the aforementioned African American English are the two often mentioned) where grammatical and lexical differences, as opposed to pronunciation, can create intelligibility issues.

Without extreme examples of what a dialect is, the word has languished in the States. A New Englander might note a Pittsburgh native’s use of ‘gum band’ to refer to a rubber band, but probably won’t associate it with the category of features that we term a ‘dialect.’ Americans tend to see such differences as isolated regional quirks more than anything else.

But perhaps ‘dialect’ will become a concept more common in everyday American conversation. Given today’s reliance on written electronic communication, we are more exposed to the grammar and lexicon of our peers, isolated from their pronunciation, than we were twenty years ago. Will we become as much aware of how our countrymen use words as the way they say them?

*I’ve previously used the term African American Vernacular English, but I’m trying the simpler African American English on for size in this post.