I first heard the word ‘dialect’ within a bizarre context. It was the 1980s, and some adult (whose identity I forget) used it as a euphemism for African American English*. It was something along the lines of, “He speaks dialect, so I had a hard time understanding him.” ‘Dialect’ needed no qualifier or article here; it was a given that this single word referred to the speech of an entire ethnicity.

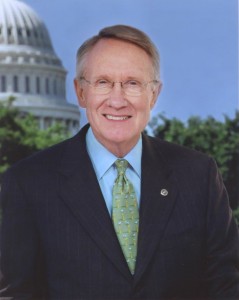

This rather icky reinterpretation of the term was revived by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid during the 2008 presidential campaign, via this cringe-inducing anecdote (here recounted by CBS News):

[Reid] was wowed by Obama’s oratorical gifts and believed that the country was ready to embrace a black presidential candidate, especially one such as Obama — a ‘light-skinned’ African American ‘with no Negro dialect, unless he wanted to have one,’ as he said privately.

Although Reid awkwardly specifies the type of dialect he is talking about, I doubt he would have mentioned a candidate’s ‘Tennessee dialect’ or ‘New York dialect’ (he probably would have used ‘accent’). The word apparently became reserved for African Americans at some point in twentieth century America. (That using the word ‘negro’ is ridiculous in this day and age should go without saying).

And this is hardly the only example of ‘dialect’ being misused (or in Reid’s case, being used correctly but cluelessly). I’d also cite an ill-informed adjunct professor of mine who once remarked, “I guess you could say an ‘accent’ is the way a native speaker says something, while a ‘dialect’ is the way a non-native speaker says something.” Ouch. Again, there seems to be a vague understanding of what a dialect is, and yet the speaker would be hard pressed to actually define it.

‘Dialect,’ I would argue, is not a household word in America. As these anecdotes suggest, it’s often misused and misunderstood. ‘Accent’ on the other hand, seems to cause no confusion, and has emerged as the more popular of the two words. This is even true of Americans’ search habits: Google Adwords’ Keyword Tool estimates about 33,100 local monthly searches for ‘British dialect,’ but a more robust 60,500 local monthly searches for ‘British accent.’

And yet you could argue that ‘accent’ is the more vague and confusing of the two terms. ‘Dialect’ describes the whole package that comes along with regional or sociolinguistic variation in a language: grammar, phonology, and lexicon. ‘Accent,’ on the other hand, really only refers to our pronunciation.

So it’s odd that of these two words, the one with the largest number of unrelated meanings won out. ‘Accent’ can be used in a number of ways in linguistics, and a whole host of other ways besides, whether we’re talking about the ‘accent’ of an interior decorating scheme, an ‘accent’ in a piece of music, or the Hyundai Accent. Type ‘dialect’ into Google, and 9 out the first 10 search results relate to linguistics. For ‘accent,’ this numbers only 5 out of 10.

To repeat something I’ve mentioned before, it’s possible America’s lack of ‘traditional dialects’ has prevented the word from taking hold. In the UK, there are dialects that sound to outsiders like separate languages (although many of them are receding), retaining features that hark back to the very dawn of the language. Here in America, a Pennsylvanian might say ‘The car needs washed’ where I would say ‘The car needs to be washed,’ but it is only in a select number of dialects (Appalachian English and the aforementioned African American English are the two often mentioned) where grammatical and lexical differences, as opposed to pronunciation, can create intelligibility issues.

Without extreme examples of what a dialect is, the word has languished in the States. A New Englander might note a Pittsburgh native’s use of ‘gum band’ to refer to a rubber band, but probably won’t associate it with the category of features that we term a ‘dialect.’ Americans tend to see such differences as isolated regional quirks more than anything else.

But perhaps ‘dialect’ will become a concept more common in everyday American conversation. Given today’s reliance on written electronic communication, we are more exposed to the grammar and lexicon of our peers, isolated from their pronunciation, than we were twenty years ago. Will we become as much aware of how our countrymen use words as the way they say them?

*I’ve previously used the term African American Vernacular English, but I’m trying the simpler African American English on for size in this post.

Ben :

During my childhood, when the dinosaurs still roamed the earth, I often heard people speak of a southern accent or a British accent – sometimes a New England accent, or a French accent. Dialect was commonly understood as referring to an African-American(they didn’t use those words) accent, a Yiddish accent, an Italian accent, etc. The common understanding of the word, as opposed to the technical definition, often referred to the way comedians put on certain skits. On Fred Allen’s radio comedy show, he would introduce one of his cast of characters with a flourish: “Here’s the Mad Russian!,” and the Mad Russian would say: “You were expecting maybe Mrs. Nussbaum?,” using a Yiddish accent and a Yiddish dialectal form of the question: “Were you expecting Mrs. Nussbaum?” Despite the dialectal form of the question, most people only heard the accent, although subconsciously I’m sure they registered the dialectal form. I think that most people still think of dialect as accent, and I don’t think that situation is going to change in the foreseeable future. In a way, it’s easier just to accept the synonomy of the two words in ordinary discourse. but I applaud your optimism.

In the theatre in North America, the terms “accent” and “dialect” are used as your professor claimed: accent is the form of language used by non-native speakers of English, while dialect is the form of language used by native speakers, especially those with regional forms, or socio-economic ones. So we have a German accent and a Maine dialect. This is NOT the pattern in the UK and elsewhere, where theatre voice professionals use the terms as linguists do: dialect is a subset of language (Mandarin and Cantonese are dialects of Chinese) while accent merely describes the sound changes that define the phonemes of any form of spoken language. Generally the term dialect is no longer used (as playwrights give the language form, and so actors need only learn the accent!)

Some will argue that the US usage pattern is derogatory, as it is used by Reid. This is certainly not the intent in the theatre, but I fear that many who use the British model assume that it is, as it has been used as code for sub-standard for many years, as in “mere dialect”.

The way I normally explain it is that you’d talk of a German speaking English with a German accent but not a German dialect.

In Britain (or at least England), “dialect” has an air of being folksy and old-fashioned, whereas “accent” can be contemporary. KM Petyt wrote that there some pronunciations that are so old-fashioned that they can only be categorised as “dialect”. As he was talking about the West Yorkshire dialect, he gave the example of [kɒɪl] for “coal”, now only used by the elderly.

As you say, the old-fashioned “feel” of the use of “dialect” in England has to do with the fact that the traditional dialects are receding fast and are being assimilated into the “neo-dialects”, regional varieties, (sometimes heavily) influenced by the traditional dialects, but much closer to “standard English”.

In other areas, e.g. in some German speaking regions, where dialects are alive and kicking, there is nothing old-fashioned or folksy to the expression – it simply means that someone is speaking a regional variety that can be quite different from the standard language.

Growing up as a Chinese-American, I always thought of “dialect” as the word that describes the distinction between Mandarin and Cantonese.

For me “dialect” is a related linguistic variety that shows differences in phonology, grammar and lexicon. The distinction between “dialect” and “closely related language” is a little blurred. For example, it is my impression that the continental Scandinavian “languages” are more closely related to each other, than some German “dialects” are, yet the former are called languages and the latter dialects.

“Accent” for me, is just a regional or individual variation in the realization of phonemes.

I know the US American English and UK English “standard” languages are often referred to as two different “accents”, but they could just as well be defined as different dialects, as they differ in phonology (not just realization, but they have a different set and distribution of phonemes), grammar (very little difference in the standards except sylistic registers), and lexicon (a number of significant differences in the words used).

I think the reason that we are more comfortable referring to AAVE as a “dialect” and to other regional variations as “accents” is due to what we notice the most.

Like you mentioned, dialect refers to all the differences, not just pronunciation. In the case of so-called accents, what we notice the most is the change in pronunciation. Yes, there are also other little differences, but when you ask someone to mimic a British accent, it is their pronunciation that will change. On the other hand, what we notice in AAVE is the change in grammar and word choice. If you ask someone to mimic AAVE, the focus of their production will be the change in syntax and vocabulary.

@Danny, I agree that linguistically speaking British and American standard English are different dialects. I think you underestimate the grammatical differences though. In ASE the past simple is used in situations that would be incorrect in BSE, and the 2nd and 3rd conditionals are formed differently (though the third conditional in some British dialects is grammatically the same as ASE, though an American might not recognise this due to pronunciation issues).

You often notice this when American actors get a British accent spot on but are let down by their script writers, who don’t get the differences in grammar. This also happens when shows deliberately search out British actors. Star trek and V for Vendetta, I’m looking at you.

This leads into @Bekah.

The reason American people don’t make grammatical changes when they “talk British” is that their exposure to British English is largely through American media representations of the dialect, which are usually scripted in ASE. Whereas they have a more accurate picture of AAVE.

African-American English is NOT correct, as there are many African Americans who speak “standard” English. The more correct term would be colloquial speech, which would encompass all the people that use language outside of the parameters of Standard English.

Pingback: Why Americans don’t understand ‘dialect’ | Language Training for Corporations & Individuals