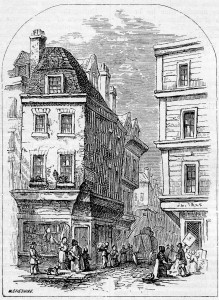

It was inevitable: if you write a blog about English dialects, eventually you will write a post about Cockney rhyming slang.

It was inevitable: if you write a blog about English dialects, eventually you will write a post about Cockney rhyming slang.

For you confused Americans out there, here is the basic jist of rhyming slang:

1.) Take any word in the English language. Like “bed,” for example.

2.) Find a two-word phrase which rhymes with this word. In our case, we might choose “soda bread” to rhyme with “bed.”

3.) When you use the original word in a sentence, replace said word with the first word of the rhyming phrase. So instead of saying “Henry, get in the bed this minute!” say, “Henry, get in the soda this minute!”

I probably mangled that. Forgive me, Londoners. I am an American who knows not what he does.

Here are some better examples:

Apples = Stairs (as in “Apples and Pears”)

Dickie = Word (as in “Dickie Bird”)

Goose = Cheque (as in “Goose’s Neck”)

Pete = Wrong (as in British DJ “Pete Tong”)

You can also say the entire phrase if you want (i.e. “It’s all gone a bit Pete Tong!”) But I don’t find that as much fun.

There are many theories about the origins of rhyming slang, none supported by much hard evidence. The first is that the slang was a way of maintaining the identity of the Cockneys, a deliberate code created to keep outsiders at a distance and maintain an upper hand on the aristocracy.

Another plausible hypothesis posits that rhyming slang began as a kind of crude business jargon. By speaking in code, storekeeps, bartenders and vendors communicated with each other and their employees without being understood by customers.

There is also a derogatory, classist explanation, which is that rhyming slang was the language of thieves. But that strikes me as part of the British upper-crust tradition of treating all lower stations as criminal.

One thing I find intriguing about the first two ideas (the “community code” theory and the “business jargon” theory) is that they remind me of theories about the origins of Yiddish. Like rhyming slang, it is often suggested that Yiddish was a way of asserting financial and cultural independence from the Germanic communities that surrounded Europe’s Jews.

Not for nothing, but East London was a major immigration point for Jews in the 19th-Century. It’s possible that Rhyming Slang was part of a broader European Jewish tradition of using language to strengthen communities and do business with hostile locals. Then again, the bulk of Jewish immigration was in the late Victorian era, long after rhyming slang had been established. So this is just speculation.

There is an unfortunate dearth of academic literature about this topic, so I open up this discussion to anybody in the know: Is rhyming slang still alive and kicking? Any other theories as to where it came from?