Growing up in Southern New England, I heard tell of a near-mythical dialect feature from Maine and other places further north: ayuh.

This word is the informal version of “yes” in Maine, and, unusually for semi-archaic dialect words, it has more of a standardized spelling than it does a pronunciation. I’ve usually heard it as eh-YUH (IPA eɪˈjʌ), but there’s also a pronunciation that puts more weight on the first syllable (EY-yuh), as well as EE-yuh or eye-yuh.

It probably goes without mentioning that Ayuh is rapidly disappearing. The word is mostly associated with the old-fashioned Down East Accent, an accent heard in Eastern Maine that, while still in existence, is pretty scarce among people under-40. While I’ve known countless New Englanders in my lifetime, I’ve never heard one utter “Ayuh.”

What I find unique and intriguing about ayuh is that it looks like the only real American relative of the aye heard in various parts of the British Isles. Most of America uses yeah, yup, yep or the African American-derived uh huh. But only in remote parts of New England does it seem a relative of aye is used.

Of course, I’d like to get out of the realm of “it appears to,” so I decided to look for some evidence of ayuh‘s etymology. Of which there is very, very … little.

In fact after going through twenty pages of Google Books results, I could only find one source remotely resembling a linguistics text that so much as mentions ayuh. That would be the awkwardly titled Facts on File Dictionary of American Regionalisms by Robert Hendrickson. Quoth Mr. Hendrickson (emphasis his):

Chiefly heard in Maine, ayuh is found throughout New England … A touch stone of New England speech, it possibly derives from the nautical aye (yes), which in turn probably comes from the early English yie (yes). Another theory has ayuh coming from the old Scots-American aye-yes meaning the same.

Now, right off the bat, I am skeptical of a book which classifies aye as a “nautical” word. Isn’t the fact that the word is widespread across large tracts of the UK and Ireland more important to mention? However, I might be willing to buy the Scottish explanation for a few reasons:

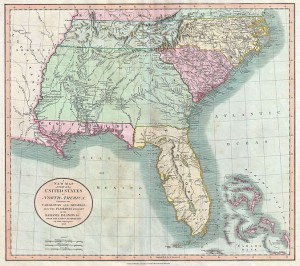

1.) Maine was one of the areas where the Scots-Irish initially settled. In fact, you can see in this map that a large percentage of people of Scots-Irish descent is found in precisely the area where the “Down East” accent is heard.

2.) In most varieties of ayuh the “ay” rhymes with “day.” This more closely resembles the modern Scottish pronunciation of Aye than in other areas where Aye is heard.

3.) The aye yes that Hendrickson mentions appear to be a feature of some Scottish English dialects to this day. Although be aware that I am deducing this from some very circumstancial evidence (such as this message board). So take this last bit with a huge grain of salt.

To be clear, I’m not 100% sure this is the only aye variant in America. Can anyone think of another? Or any type of aye outside the British Isles?