I would be remiss not to mention this week’s news story about an Oregon woman who woke up from surgery speaking a different accent (Check out the stunning video clip of her speaking).

This lady suffers from a rare condition called foreign accent syndrome (FAS), whereby a brain injury (or some other phenomenon) affects the speech centers of the brain. It results in the unconscious adoption of something resembling a foreign accent. Here is another prominent case of this:

Some headlines implied the Oregon woman woke up with a specific accent (e.g. “Woman wakes up from surgery with British accent”). Anyone with the slightest knowledge of English dialects will see this is not the case: FAS sufferers are afflicted with strange speech traits that may coincidentally sound like a particular nationality, but they actually have an idiolect entirely unique to them.

Because so few people actually have FAS, there isn’t a wide body of research about it. So this story got me thinking: Many of the people I interact with on this site have a fairly extensive knowledge of phonetics and accents. If I or another phonetics obsessive were to get FAS, how would it affect our speech?

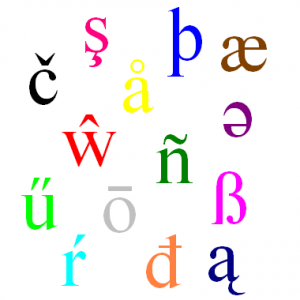

At the risk of sounding cocky, I’ve used the International Phonetic Alphabet for so long that I read it as easily as I read the newspaper. When I look at three basic vowel sounds transcribed in IPA–say, ɑ, i, and u– it seems unthinkable that I would lose knowledge of these symbols and what they mean. I’m good at imitating dialects as well: wouldn’t this knowledge survive?

This may be wishful thinking, though. Is it possible that if I had Foreign Accent Syndrome, I might believe ɑ to represent some other vowel? Would I be able to “put on” a standard American accent and cure myself? Or would all knowledge of accents and their phonetics be wiped clean?

I believe that those of us who have an intense obsession with phonetics perceive language in different ways. We codify spoken language on two different levels. As such, our relationship to speech is different, even if this difference is slight.

Would this special relationship survive the kind of trauma associated with Foreign Accent Syndrome? Or is our knowledge much more fragile that we assume?