Some dialect phrases are so parodied that you question whether they have any basis in reality. Note Irish ‘top o’ the mornin‘ (mostly fiction), Australian ‘g’day‘ (mostly fact), and Cockney ‘guvnor‘ (based in fact, but passé). I would add to this list ‘fuhgeddaboudit,’ a New York Italian-Americanism. You can hear an exaggeration of this idiom at 1:27 in the trailer for the Hugh Grant flop Mickey Blue Eyes:

(I’m confused as to why James Caan is schooling a British RP speaker on the finer points of non-rhotic speech, but anyway …)

‘Fuhgeddaboudit’ seems to have become a pop cultural meme around the time of the 1997 film Donnie Brasco. Here’s a quote from Johnny Depp’s character on the phrase’s meaning in mafia culture:

‘Forget about it’ is like if you agree with someone, you know, like Raquel Welch is one great piece of ass, ‘forget about it.’ But then, if you disagree, like a Lincoln is better than a Cadillac? ‘Forget about it!’ You know? But then, it’s also like if something’s the greatest thing in the world, like mingia those peppers, ‘forget about it.’ But it’s also like saying ‘Go to hell!’ too. Like, you know, like ‘Hey Paulie, you got a one inch pecker?’ and Paulie says ‘Forget about it!’ Sometimes it just means, ‘forget about it.’

Does anyone in New York actually demand that one ‘fuhgeddaboudit?’ It’s a tricky question, since ‘fuhgeddaboudit’ is just a transcription of ‘forget about it.’ And that’s a common phrase in English, after all.

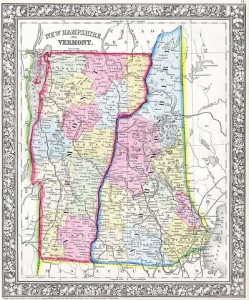

While I’ve never heard someone in New York say ‘fuhgeddaboudit’ specifically, I once heard a man speaking (probably dialectical) Italian in Brooklyn insert the English loan ‘don’t worry about it,’ pronounced rather like dɔn waɹi ba:ɾ et. (Note that ‘bout is pronounced with a:). Although it’s not the same phrase, the anecdote makes me wonder if it’s possible ‘fuhgeddaboudit’ was borrowed by Italian (or Sicilian) speakers, then loaned back to English after accruing hints of foreign inflection and phonology.

But is ‘fuhgeddaboudit’ actually common in New York-Italian speech? Donnie Brasco is based on a non-fiction book of the same name, and a quick Google Books search of the text yields dozens of ‘forget about its.’ That being said, I couldn’t find anything like Depp’s semantics lesson in the book. Has anyone heard an authentic ‘fuhgeddaboudit?’