A commonly held assumption is that New England accents are cousins of East Anglian accents in the UK. It’s an impression shared even by non-linguists, as this interview with British actor Tom Wilkinson from some years back attests (he discussed hanging out with Maine locals while shooting In the Bedroom):

A commonly held assumption is that New England accents are cousins of East Anglian accents in the UK. It’s an impression shared even by non-linguists, as this interview with British actor Tom Wilkinson from some years back attests (he discussed hanging out with Maine locals while shooting In the Bedroom):

“The accent they have, the broad Maine accent, is much closer to an English — it’s like a brother to the Norfolk accent. Those guys could walk into somewhere in East Anglia and people would think they were local.”

So is there a clear connection between the two?

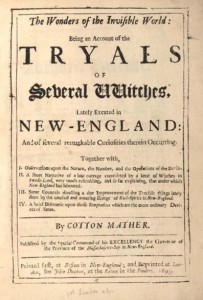

The reason for the supposed similarity is that many of the original New England settlers reportedly hailed from East Anglia. I can’t comment on this claim; my knowledge of historical demographics of this sort is hardly robust. I would note, though, that when I researched the Salem Witch Trials in high school, the ancestries of its participants struck me as more diverse than that. Many bold-faced names in Salem had family from London, Lancashire, Derbyshire, Somerset, Norfolk, and any number of other places.

It is certainly true that both a New Englander and an East Anglia might utter the classic phrase ‘Park your car in Harvard Yard’ similarly: with a centralized or fronted [a] sound that might give the impression that ‘park’ is pronounced like ‘pack.’ This feature is shared by many other accents, of course, so this alone doesn’t immediately invite comparison.

Likewise, both East Anglia (well, most of it) and Eastern New England are non-rhotic, meaning the /r/ is dropped at the end of words like ‘car’ and ‘better.’ Again, not a very compelling piece of evidence.

Like a lot of trans-Atlantic comparisons, this one seems to work best when you’re comparing rural, isolated accents and not metropolitan ones. If you compare a Bostonian to someone from Norwich, you’re unlikely to find much common ground. But listen to this Maine Lobsterman from the far East of the state, and I can see how Wilkinson’s statement makes some sense:

Then compare this to an old (and possibly not entirely authentic) recording of a man from Norfolk:

See any similarities? I like to exercise caution with claims like these, since so much has changed about the English language since the time of the Massachusetts Bay colony. I defer to anyone who knows a bit more about early American immigration patterns.