Kristin Dos Santos / Wikimedia

USA Today ran a piece yesterday listing the top five American accents done by British actors. While I am unfamiliar with the number one actor on the list, Jamie Bamber, I’m glad to see that Hugh Laurie and Idris Elba are represented: both actors who have done fantastic dialect work.

Continuing this meme, here is my own list of the top 10 non-Americans who have excelled at British American dialects.

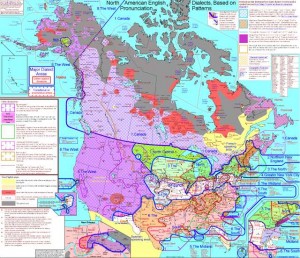

1.) Idris Elba, The Wire. It was hard to pick number one, but at the end of the day, this British actor won out. He didn’t just do any American accent on the wire. He mastered, from top to bottom, the variety of African American Vernacular English spoken in West Baltimore. It is some of the most masterfully specific dialect work I’ve ever seen.

2.) Hugh Laurie, in House. There is a debate about the authenticity of Hugh Laurie’s accent on this American TV show. Personally, I don’t think authenticity is what makes this fake accent seem so real. It’s that Laurie realizes that Americans can be just as witty, ascerbic and cutting as Brits. Laurie gives the accent a refreshing intelligence and vigor.

3.) Heath Ledger, in basically anything. What was great about this late Australian actor was that you never noticed that he was doing a dialect. Ledger created characters, from Ennis del Mar to the Joker, with voices so developed that the whole notion of “putting on an accent” was an afterthought.

4.) Toni Collete, in the Sixth Sense. Collette’s accent work is always phenomenal, but her work in the Sixth Sense impressed me for one reason. She is basically the only actor, ever, and I mean EVER, who has grasped the fact that Philadelphia actually has an accent. She could have done some standard American something or other, and would have been fine. But no. It’s that attention to detail that separates sublime dialect work from the merely competent.

5 & 6.) Guy Pearce & Russell Crowe, LA Confidential. Continuing the theme of “Australians do the best accents” is this one-two punch of Aussies in this 1997 crime drama. Like a lot of actors on this list, these two layered in lots of great character work: Crowe was rough and grizzled, Pearce uptight and bookish. And they fit into the period and milieu perfectly.

7.) Naomi Watts, in most things she’s in. I have to give props to this Australian actress, who has played Americans more than she has Aussies and has never once slipped. Extra points for being able to handle some seriously emotional material while donning a different accent than her own.

8.) Daniel Day-Lewis, Gangs of New York. Day-Lewis did not use an actual dialect in this movie, but rather a faschinating interpretation of how a New Yorker would have spoken in the mid-19th-Century. The dialect coach working on the film spoke of trying to return the accent to its roots in British English and Dutch, and Day-Lewis nailed this concept beautifully.

9.) Christian Bale in Rescue Dawn. Bale’s accent work can be hit or miss, not the least because, given his international upbringing, I have often questioned whether he has a natural accent. However, I thought his dialect work in Rescue Dawn was excellent: he didn’t just do an American dialect, but actually managed to add just the perfect hint of a German influence. Another of those small details that really steps things up.

10.) Tracy Ullman on the Tracy Ullman Show. This now-forgotten show (the inauspicious birthplace of the Simpsons) featured the superb dialect abilities of Tracy Ullman in a variety of characters. All flawless.

What actors do you think do great accents?