I’ve used the term Estuary English quite a bit on this site. For the dialect novices out there, I’d like to explain what this phrase means, and my personal take on it.

I’ve used the term Estuary English quite a bit on this site. For the dialect novices out there, I’d like to explain what this phrase means, and my personal take on it.

Estuary English is a hard concept to define. Sometimes it’s referred to as a contemporary “standard British accent;” other times as something more regional. So before I go further, let’s look at the original definition of Estuary English, proposed by linguist David Rosewarne in 1984:

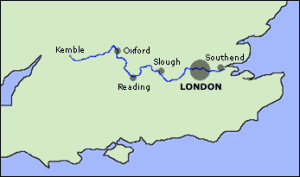

“Estuary English” is a variety of modified regional speech. It is a mixture of non-regional and local south-eastern English pronunciation and intonation. If one imagines a continuum with RP and London speech at either end, “Estuary English” speakers are to be found grouped in the middle ground.

The heartland of this variety lies by the banks of the Thames and its estuary, but it seems to be the most influential accent in the south-east of England.

As Rosewarne and other linguists suggest, Estuary is a type of accent found in Southeast England. Notably, it is found in parts of the region beyond London itself: Essex, Sussex, Kent, Berkshire, and such.

For an example of Estuary, I often use comedian Ricky Gervais, whom I would consider an Estuary speaker, from Reading:

It is hard to pinpoint what Estuary is, but linguists tend to mark it by a number of features:

–T-Glottaling: The ‘t’ in a phrase like “lot of” becomes a glottal stop [ʔ] (“lo’ of”); this may occur in words like “butter” as well (although this point has been debated a good deal).

–L-vocalization: The ‘l’ in words like “bell” becomes a vowel sound (“bew”).

–The London Vowel Shift: Estuary participates in a vowel shift typical of London, whereby the vowel in FACE moves toward the vowel in PRICE (hence “lace” moves toward “lice”); the vowel in PRICE moves toward the vowel in CHOICE (so “buy” moves toward “boy”); not to mention several other shifts too numerous to mention here. (You can see a more detailed description of Estuary’s phonetics in this John C. Wells article.)

A valid objection to the concept of “Estuary” is that many of these features existed throughout Southeast England long before contemporary times. In other words, these were never exclusively “London” features, and many of the areas where “Estuary” has been observed have had similar accents for at least a century.

But that’s not the point of the Estuary distinction. At least not in my opinion. What makes the accent interesting is that people who in previous generations would have spoken Received Pronunciation or perhaps near-RP (standard British English) have instead opted for this more “regional sounding” accent. Estuary isn’t radical because of its spread; it’s radical because of the type of people who speak it: middle-class young people, celebrities, and white collar professionals.

Estuary is also perceived, by some, as a phenomenon moving throughout the UK (not just the Southeast). This is a problematic notion, since many features of London English coincide with those of other accents: a similar vowel shift to London’s can be found in the Midlands, and t-glottalling is a traditional feature of accents as disparate as those in Manchester, Scotland and Dublin.

One feature that is almost inarguably spreading, however, is l-vocalization.* However, given that this feature has become fairly standard in genteel accents (I often use Tony Blair as an example), is this indicative of the spread of Estuary? (Whatever that means). Or is l-vocalization becoming something of a prestige feature?

As Estuary English is a very abstract concept, I have a hard time answering these questions. I think there are features spreading rapidly throughout the UK that indeed seem to gravitate from Greater London. Given that the region now accounts for a good 20% of the UK’s population, this is not very surprising. But can these trends specifically be attributed to “Estuary?”

NOTE: I removed a video clip from this post in a later revision (although it’s referenced in the comments). It’s authenticity was debatable, and as it didn’t really add anything to the discussion, I took it out completely.