While we’re on the topic of rhotic and non-rhotic accents, I’ll address a frequently asked question: why do non-rhotic accents switch so quickly to rhotic? And vice versa?

While we’re on the topic of rhotic and non-rhotic accents, I’ll address a frequently asked question: why do non-rhotic accents switch so quickly to rhotic? And vice versa?

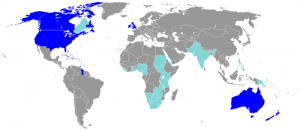

Since World War Two, both the US and Britain have experienced massive changes in the distribution of rhoticity and non-rhoticity (i.e. whether or not the ‘r’ is pronounced in ‘car,’ ‘core,’ ‘father,’ etc). In some regions in America (e.g. areas of Maine), local accents have changed from one to the other within a single generation. And I’m sure the converse is true on the other side of the Atlantic. So why does this feature seem so fickle?

As with many questions of dialect change, I’d say the answer is ‘children.’

Before expanding on that point, however, I should say this: rhoticity and non-rhoticity are not as easy to ‘learn’ as one might think. As a young actor learning British Received Pronunciation, I struggled with non-rhoticity. I found dropping the /r/ in words like ‘skipper‘ and ‘particular’ fairly simple. But for words like ‘cart’ and ‘park,’ I found it difficult to reorganize the phonology of my accent so that ‘car‘ uses the same vowel as ‘father.’ And don’t get me started on words like ‘nurse:’ as an American, the concept of an elongated schwa-like sound was foreign to me.

I’m sure it’s no different for a British actor learning a rhotic accent. She would have to adopt an entirely new phonological structure, splitting her ‘long-a’ into two different phonemes. Again, not as simple as it seems.

Likewise, it’s more difficult for children to change their accent from rhotic/non-rhotic to non-rhotic/rhotic than it is to pick up many other accent features. And if children have a hard time mastering a feature, it’s a recipe for dialect instability. Linguist J. K. Chambers, to cite an example, did a study of Canadian children who immigrated to Southern England. 55% of his subjects managed to eliminate t-flapping (i.e. pronunciation of ‘butter’ as something like ‘budder’); by contrast, only 8.3% of his subjects had switched from rhoticity to non-rhoticity.*

If children have a hard time switching from rhotic to non-rhotic, then it follows that even a modest amount of inmigration might disrupt the balance of non-rhotic and rhotic accents in a community. It seems likely that a decent proportion of children who have moved to a new place will maintain the rhoticity or non-rhoticity of their upbringing. This can hugely alter the dialect landscape of their new home. It’s not just adult transplants who can impact the rhoticity of local speech; it’s their offspring as well.

Compounding this effect is the fact that the children of newcomers often account for a disproportionate share of a community’s youngsters. Hence transplants, in my opinion, are more likely to produce the next generation of linguistic innovators than ‘locals.’ And so accents switch from rhotic to non-rhotic more quickly than with other dialect features.

I think, for now, that this rapid switching is starting to level off. Here in the US, we just don’t have enough non-rhotic accents anymore to create an American renaissance of non-rhotic speech. Meanwhile, rhotic areas of England have remained fairly rural, preventing rhoticity from spreading there.

The only way I can see this changing is if, for some reason, there is a large influx of Brits to America, or a large influx of Americans to the UK. Only time will tell, but I don’t see that happening soon.

*Chambers, J.K (1992) “Dialect Acquisition” in Language 68 pp. 673-705.