Years back, an actor asked me a dialect ‘riddle’ of sorts: is there any vowel represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet that does not exist in any accent of English?

I don’t know how to answer that question; it depends on what one means by a vowel ‘existing’ in an accent. All languages, and their dialects, feature ‘allophones.’ That is, each speaker of English pronounces individual vowels of the language in several ways. And English exhibits seemingly infinite variety when it comes to vowels. (Depending on the context, I probably pronounce the vowel in ‘but’ with four vowels)

Conversely, it’s worth noting that we represent many English vowels with IPA symbols that don’t entirely correspond with their pronunciation. For example, we denote the General American ‘a’ sound in ‘father’ with the symbol ɑ. This indicates an open, back vowel, a bit like the ‘aaaaah’ you make when you yawn. Most accents, however, feature a vowel that is in fact pronounced with the tongue somewhat more front in the mouth: those with the fully back ɑ are probably in the minority.

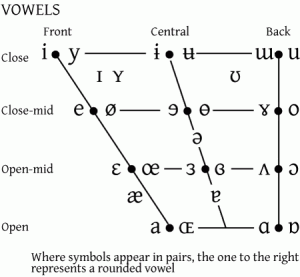

So as the last two paragraphs suggest, to say that a vowel ‘exists’ in an accent is to make an overly vague statement. But taking a quick glance at the IPA Chart, my tentative impression is that there are very few vowel sounds that don’t occur in at least some accents of English.

Even the exotic front rounded vowels get some play (for example, in the New Zealand pronunciation of ‘nurse’). With all of English’s vowel shifting, it’s not surprising that the rarest of phones appear on the lips of Anglophones somewhere in the world.

I’d say if there is one sound even arguably unheard of in English accents, it’s that represented by the IPA symbol ɯ — a sound essentially like the pure /u/ heard in Spanish or Italian, but without rounded lips. Even in that case, I’m not so sure: this vowel appears in some dialects of the Irish language, so I wouldn’t be surprised if some types of Irish English use it as well.

But this might be a meaningless quest: IPA symbols don’t have an easy one-to-one correspondence to the sounds they represent. So as much as I hate to say it, the original question is perhaps unanswerable.