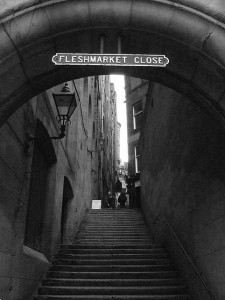

I’m reading (and enjoying) my first Inspector Rebus novel, Fleshmarket Alley, by Scottish crime writer Ian Rankin. Non-American Rebus fans may not recognize the book’s American title, as it goes by the more evocative moniker Fleshmarket Close in the UK. Why it must be spelled out this way for Americans is anyone’s guess; the context more than clarifies the term’s meaning in the book.

Alas, this is hardly the first time editors have reworked a book’s language for American readers. The Harry Potter Lexicon lists many such alterations to the series’ North American editions. The changes are especially pronounced in the early entries, but can be found throughout the series (although given that American readers bought the Trollopian later volumes in droves, I doubt the odd “crumpet” would keep fans at bay).

Some such changes to J.K. Rowling‘s oeuvre made sense (e.g. “disorientated” strikes most Americans as strange). Others induce groans among those passingly familiar with British English (“Parking lot” replaces “car park?” And for Pete’s sake, “soccer” instead of “football?”)

Then there are the ridiculous switches in the American Potter whereby overzealous editors replaced words native to American English: “lavatory” is at one point changed to “bathroom,” “sweets” becomes “candy,” and “cinema” becomes “movies.” Such finickiness recalls Ricky Gervais’ shock at the inclusion of “Shakespeare” in the British English glossary provided with the The Office‘s American DVD. (Surely we aren’t that clueless.)

For whatever good intentions such edits may spring from, they drive me crazy as a reader. Fleshmarket Alley/Close, to cite one example, makes effective use of its Edinburgh locations. So when the protagonist refers to “Edinburgh’s tenements,” for instance, is this the word Edinburghers use (it would be interesting to compare the Scottish and American definitions), or was it something else in the original? A mere Google search reveals the answer, but I’d like to feel I’m reading the author’s original words. In Rankin’s novels, so Scottish you can feel the chilly damp stinging your cheeks as your read them, the dialect and language is as much a part of the atmosphere as the fog-shrouded Firth.

I’ve long assumed this to be a recent trend, but I’ve begun to wonder how much non-American literature I’ve read that’s been tampered this way. Does anyone know the history of this kind of thing? Or other books that have been “Americanized?”

I’ve heard a lot about how British publishers and media like to enforce the idea at home that Americans are incredibly stupid and/or ignorant. Either the Sun and the Daily Mail suggested that Downton Abbey’s pilot only included a recap on the legal practice of “entail” because thick Americans wouldn’t understand what that was. Never mind that it’s an archaic law abolished in the 1920s, nor that Americans are stereotyped over there as being well-versed in legal matters.

There’s also a problem of not knowing which Britishisms Americans would or wouldn’t understand. We all know that football is soccer, but what’s a counterpane?

~s~

Perhaps excepting a title (for advertising reasons), can’t people be expected to use a dictionary? Or these days Google, for Pete’s sake. It’s what I have to occasionally do with AmE books as a BrE native; it’s not difficult and even if it were, providing a glossary or footnotes would patronise the reader far less than bowdlerisation by unnecessary translation.

That’s my feeling as well. I recall a few books that have glossaries, but they’re usually those written in extreme dialects or con-lects (like some editions of A Clockwork Orange).

It’s interesting that you bring up Harry Potter as an example. I checked out all seven books from American public libraries, so I assume I was reading the American versions. Even so, there were numerous cases where I had to look up a word or term.

Out of sheer geekiness and curiosity, I even started keeping a list for books 5 through 7. Between those three books, I counted about 100 terms/phrases that I had to look up! They ranged from “taking the mickey” to “builder” to “rucksack.” These may seem obvious to you, but I honestly wasn’t familiar with their usage. (To be fair, in many cases I could guess the meaning from context, but it still sounded strange to my ears.)

In one earlier book (book 3?) I remember Hermione used the term “brainwave” towards the end of the book. I immediately assumed that this was some sort of “wizarding world” term and frantically searched my memory for mention of this particular spell — and I was quite disappointed in myself since I usually pride myself on being fully on top of the lore details of any fantasy/sci-fi book I’m reading. I finally realized that “brainwave” is a simple British word.

I’m NOT suggesting that I support changing books for an American audience — I also strongly prefer subtitled to dubbed movies. But I don’t think you should underestimate the potential inconvenience for an American reader. I often read with my computer nearby, but not always. (Perhaps for people using e-readers this is a non-issue.)

After book two, I believe they scaled back these types of edits. It was clearly in the first slim volumes that they went for a kind of dialect neutrality. Although even in book two, there’s no mistaking you’re in Britain when an important plot point centers around a Ford Anglia!

Imagine Irvine Welsh for Americans. That would make me cry.

Ugh, me too. That would be … well, not Irvine Welsh, that’s what.

I don’t think the “cinema” and “sweets” replacements were intended to aid comprehension. Rather, the editors were trying to make the reader forget this story took place in England. They wanted readers to feel like they were reading “normal” language, and so words that weren’t in Standard American common usage got the boot. I’m glad they toned down the Americanization in the later books (even to the confusion of people who didn’t know that “candyfloss” meant “cotton candy”), so we Americans can get a chance to add some British English words to our vocabularies.

That’s probably true, but it’s still a strange choice. I’ve found Englishness to be something of a selling point for many children’s novels; there was never any ambiguity that Wind in the Willows, The Secret Garden, or the Narnia books were British. Which is why the attempt to make the nationality of the Potterverse ambiguous struck me as unusual.

I’m glad you mentioned Harry Potter, the strangest change of all was “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” becoming “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”, at least in early editions. That, for me, suggests that American publishers have an insultingly low opinion of their younger readers.

I feel sorry for American readers in this case, one of the interesting things about reading American books is that it gives you a window on a different world. The strangeness and difference is part of the fun. That some cultural gatekeepers think that they have to be protected from this is very sad.

The philosopher-sorcerer switch was especially bizarre. That seems less to do with whether children understand what “philsopher” mean, and more because “sorcerer” is better for marketing purposes.

I think you might be right, but it’s still a big jumpof logic… “Who’ll buy a book with philosopher in the title?”

Well lots of folk, including American kids.

Even if they did understand what “philosopher” meant (which I probably didn’t when I was 6), I don’t think the word means what it normally means in that context. It most likely means “an alchemist or occult scientist”, a definition which Dictionary.com calls “obsolete”. I wasn’t familiar with that definition until I looked it up just now (I’m in my 20’s). But maybe that meaning isn’t obsolete in the UK.

On the other hand, though, you wouldn’t have to be familiar with that definition of “philosopher” to understand what “the philosopher’s stone” was. It could have been called “the amazing stone”, as long as J.K. Rowling made it clear in the book what it’s purpose in the story was. So I don’t see why they thought they had to change the title for American children but not for British children. It may have been for the reason you say.

This edit is truly bizarre because they changed it from an “existent” item to a non-existent one.

The Philosopher’s Stone, in alchemy folklore, allows one to change junk metal into gold through contact. (I’m simplifying things here). The Elixir of Life grants youth and vitality. The alchemist’s dream is to possess these two items.

Changing it to “Sorcerer’s Stone” because the book has magic is like changing the “Ford Fiesta” to “Ring-road Fiesta” in Britain because you drive it on roads.

I’m sure the people responsible for the Harry Potter edits didn’t know the significance of the Philosopher’s Stone.

The biggest thorn in my side with these is the Millenium Series (was that title so bad????). Not just is it illogical, not only does it obscure the themes of the books, but it’s downright sexist. Books that are all about the ghosts of the past, lingering Nazis, and institutional as well as personal misogyny are called “The Girl……”

The first book was “Men Who Hate Women”. It may have been a bit plain, but the books are for adults. In its place the arbitrary Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I thought the book was going to be some Occidental-penned Oriental exoticism book involving a murder mystery over a dead hooker written by someone who doesn’t know that usually only Yakuza would every get big tacky tattoos.

It’s like renaming Ken Burns’ series on jazz as “The Boys with the Brass Instruments”. I’m sure if Stieg had not died such an unfortunately premature death he would have protested.

I meant to place that last comment on its own, not as a reply; oops.

There was a time when publishers didn’t assume that kids are both ignorant and too lazy to become otherwise. An entire generation of American children learned about alchemy from the Donald Duck and Scrooge McDuck comic-book story “The Fabulous Philosopher’s Stone” by Carl Barks that appeared in the June 1955 issue of Uncle $crooge. Barks made a point of never talking down to his juvenile audience, many of whom were in fact 5-to-7 year-olds first learning to read from his comic books, and his publisher (Western Publishing, under the “Dell” imprint) agreed. The first- and second-graders of the time were not turned off by the word “philosopher”, even if it took them some time to figure out how to read it! Would that modern publishers held that same attitude towards their young audience!

BTW, I seem to remember that the Portuguese translation changed “Platform 9 3/4” to “Platform 9 1/2”.

Ben:

It’s all about money (aren’t most things?). The publishers have had this convention for many years. They assume that readers will be turned off by words and phrases that may stop the flow of the narrative.

At the same time, there is the elitist attitude among some of the literati, that folks out there in fly-over land are unsophisticated: for example, if the inspector, in dialogue, refers to “you lot,” obviously, the editor is going to change it to “you guys,” or some other “American” locution.

Synonymous words and phrases from another dialect may be worrisome to the naive, but interesting to others. As Casey Stengel said, “You can look it up.”

I don’t know when this trend started, but as an American reader, it annoys the heck out of me (and that’s putting it mildly.)

It makes me sad to think how many American children lose their chance to explore the rich variety of English languages when they are subjected to Americanized Harry Potter books and others. Why not let them learn early that “trainers” are what we call “gym shoes” – or “running shoes, tennis shoes, sneakers, kicks”? If they can learn American synonyms and usages, surely they can pick up some British English without their brains overheating. American publishers are selling their readers, young and old, short, and I think it’s shameful.

Personally, I know my interest in English language differences was piqued when I was very young; I had no more trouble “decoding” the language of Lewis Carroll, A. A. Milne, and P. L. Travers than I did that of L. Frank Baum, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and E. B. White.

I order my English, Scottish, and Irish books from overseas suppliers, or pick them up myself when I am overseas. I want my Rankin in Rankin’s own words, thank you very much.

I couldn’t agree more. I think it’s important for children to be introduced to language outside the type they’re used to: the ability to understand and tolerate unfamiliar language is our most valued skills as readers.

I agree. When I was obsessed with the Harry Potter books (right around the time the 7th came out) I waited until I was visiting family in India to buy them, because it just adds a sense of magic (in my humble opinion) to read them the way they were originally written, and 6th-grade me had zero trouble understanding them.

There’s a children’s book from a few year’s back called Everything on a Waffle by Polly Horvath, which takes place in Coal Harbour, British Colombia. The American edition consistently and correctly spelled the city name with the “u”, but this year, a sequel came out called (in the American version) A Year in Coal Harbor. I mean, come on – surely we Americans are not so dense that we couldn’t have figured out that Harbour meant Harbor.

All books written by Brazilian Paulo Coelho are Lusitanized / translated into Continental Portuguese in Portugal. Not only spelling is changed, and Brazilian words/expressions, but syntax and word order too. I guess Portuguese people wouldn’t like to read it in Brazilian Portuguese originals.

Wow, that’s odd. It apparently used to happen in the UK in the ’20s, but I don’t think spelling is even “corrected” any more.

Somewhat off topic, but since so many commenters are complaining about the issues of assumed ignorance and insulted intelligence, I thought I might post this great David Mitchell clip:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QjG9JcyLYbw&w=560&h=315%5D

This is entirely off topic, but I recently bought your guide to the British RP accent, and found it so helpful! I could already do a decent one, but I definitely learned a few new things and gained a lot of confidence. I used it all day at work and even had a conversation with a very nice lady who used to live in England, and she was completely convinced that I’m from England. Great guide! I really hope to see one for a Scottish, Estuary, or Irish accent soon. It’s become a bit of a hobby of mine to try to escape from the unmusical quality of my everyday GenAm.

On another completely unrelated note, I noticed you pronounce your R’s very strongly when doing words in an American accent. Is this just for the sake of the guide or is it how you normally speak? I’m asking because I don’t normally hear R’s pronounced that much, even though people around me pronounce theirs more than I do. (Indian parents = hint of mid-Atlantic in some of my words. I’m told occasionally that I sound a little British)

Pingback: This Week’s Language Blog Roundup: Dictionary scandal, names, 30 Rock cocktails | Wordnik

I’m a little late to this discussion, but I just noticed this fact. Joe Hill’s next novel is going to be called NOS4A2 in the U.S. and NOS4R2 in the U.K. The reason for this is very much connected to the subject of this blog; I’ll let you figure out the details.

Apparently Joe Hill explained this was due to the way it’s pronounced differently in the two regions. But all examples I can find of American pronunciation are the same as British pronunciation – /nɒsfərɑ:tu:/ that’s a as incar, not /nɒsfəreɪtu:/ with a as in late. Or am I missing something?

My thought process as an Oklahoman:

NOS4A2: en oh es four ei two => Oh! s-four-*-tu sounds like Nosferatu, he must mean A as in father.

NOS4R2: en oh es four are two => Wow, that sounds even more like Nosferatu, just with an extra R sound.

Would I have recognized it without reading the first one first? Probably, it is actually closer even with the extra letter, and when you realize that in an r dropping dialect it would be even closer than that, it was probably the original, and the publishers just didn’t respect my ability to recognize the name with the extra r in the way. Perhaps they didn’t realize that Americans would pronounce the first as Nosfereitu (where the ei is representing the sound a as in late). It does seem incredible that someone would think a as in late sounds closer to a as in father than are as in the letter r, but if they haven’t heard too many Americans and don’t respect our intelligence to boot, then perhaps it is explained. Or perhaps they believe (incorrectly in my case at least) that Americans pronounce Nosferatu as Nosfereitu. It is possible that there a number of Americans that pronounce it that way. I haven’t met them, but there are a lot of people I haven’t met, and I have often met people who pronounce less used words differently than I do.

As an Edinburgher, I can assure you that it would have been ‘tenements’ in the original. It’s a word used much more in Scotland than England, for the sort of tall buildings with flats that you can see in the background of the photo. These are typical of Edinburgh’s Old Town, which is full of ‘wynds’ and ‘closes’ like Fleshmarket Close.

But more generally, can you imagine the opposite happening? Grisham, Ellroy, Chandler etc being ‘translated’ into BritishEnglish. I can’t imagine what would happen to Mickey Spillane! In fact, does this ever happen in reverse, apart from the odd spelling change?

There’s also the point that much in the Rebus books is just as foreign to English readers as to Americans; do they get a different version? Of course not. And as for Trainspotting? But I see Charles Sullivan got there before me.