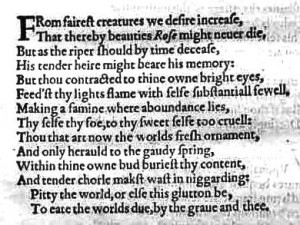

One of the incidental pleasures of reading Shakespeare’s sonnets is finding rhymes that give us clues about Elizabethan English. One of these occurs in the first four lines of the entire collection:

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

“Die” and “memory” are clearly not “eye rhymes.” In Shakespeare’s day, these two vowels would have been pronounced with a somewhat closer pair of vowels, probably something like ɘi for “die” and i: “memory.” So this would have been a more plausible oblique rhyme than it is today (for most American and British accents).

Such wordplay has been an excellent tool for historical linguists, validating important hypotheses about the Great Vowel Shift, the pronunciation of Middle English and other developments. So I sometimes wonder if, hypothetically speaking, historical linguists hundreds of years from now could deduce anything important from rhymes in our era.

Of course, it’s likely that such scholars will have far, far more written and recorded evidence of how their ancestors spoke than we do. But if, tragically, the entire internet were wiped clean and some future prescriptivist dictator were to destroy all writing about linguistics, would rhymes reveal anything about 21st-Century English speakers?

It likely depends, of course, on how much the language changes. One would also have to rely mostly on song lyrics, since rhyming poetry is not exactly the dominant literary form of the 2000’s. And although I can’t say what kind of pronunciations 25th-Century English speakers would find unusual, I can think of a few examples of lyrics that say something interesting about particular dialects of English.

Take, for instance, this snippet from Kanye West’s “Gold Digger:”

Eighteen years, eighteen years

And on her 18th birthday he found out it wasn’t his

West here rhymes “years” and “his,” because in some varieties of African-American English, the two vowels in these words are nearly neutralized in phrase-final or emphatic positions. The vowel in “his” is tensed and becomes something of a centering diphthong along the lines of iɪ, making it sound quite close to the vowel in “years.”

Of course, you would need more evidence to actually deduce this. Technically, this rhyme might also work for certain British accents, but for the opposite reason: the vowel in “years” can become a long monopthong with a similar quality to “his” (i.e. ɪ:). Which points out the main caveat of relying on rhymes: they can never serve as the sole piece of evidence in detective work like this.

Can anyone think of other contemporary lyric rhymes that suggest salient things about English today?

In songs written (and performed) by US artists, ‘love’ always rhymes with ‘of’.

In my accent, these words never rhyme.

Slightly tangential, but this post reminded me of Eminem rhyming “orange”:

http://youtu.be/eRX8sXdCkfo?t=33s

Also tangential, but my favorite way of rhyming “orange” is to create a broken rhyme of sorts in which you incorporate the first consonant of the second line. I.e. “The sun was orange / till it started porin’ / Just as the guests arrived”

Nothing in current music springs to mind for me, although, of course, the Beatles felt free to write this “rhyming” couplet:

“People running ’round, it’s five o’clock /

Everywhere in town it’s getting dark.”

I had an English Literature professor who was a bit pretentious when it came to Shakespeare. She would actually pronounce the “y” in “memory” to rhyme with the modern pronunciation of “die”. I’m fascinated to see that you’ve uncovered the truth, as well as it can be known. (I just read all of the sonnets a couple of years ago; very rewarding, but full of oddities like the one you mention, plus endless usage in the early ones of winter, spring, and summer as metaphors for age.)

The clock/dark “rhyme” could be the result of imposing the (US) father-bother merger upon a non-rhotic (Liverpudlian) accent.

Adele’s “Rumour has it” rhymes “real” and “will” which wouldn’t rhyme in my accent (the vowels being [i:] and [I] there).

She, she ain’t real

She won’t be able to love you like I will

Collin – callin’

Paul – pol

The Venga Boys’ We Like to Party:

http://www.angelfire.com/music/lyricsHERE/Lyrics/w/WeLikeToParty.html

“so if you like to party

come on and move your body!”

non-rhotisism and intervocalic voicing turn party in “pa:di” (or pa:ri?), which rhymes nicely with body “ba:di”

ɾ for the flap/tap d or t, never r. So [pa:ɾi]. Though “pa:di” works well enough in this sort of context, I think.

party/body rhyme is common in NYC & NJ accents (think of Fran Drescher)

The problem with this fact is that party can then sound like potty.

It’s noticeable in the Aqua song “Party Girl” where the lead singer (who is Danish, but putting on a NYC accent) says “Come on Barbie, let’s go party” but it sounds to me like “Let’s go potty”.

I can’t think of any lyric rhymes at the moment, but John Wells did a post about jokes that don’t work in some dialects:

http://phonetic-blog.blogspot.com/2011/03/funny-har-har.html

I myself didn’t get the pun in “Shaun the Sheep” until my wife pointed it out – a non-native speaker, she had learned a standard RP as her first accent.

You could write a whole dissertation on Watch the Throne.

One favorite is the vowel in Jay-Z’s rhyme of “here” with “fair”:

“Ball so hard, since we here / It’s only right that we be fair”.

It doesn’t look like it rhymes on the page, but it totally works in the song!

Pingback: This Week’s Language Blog Roundup: dialect maps, geek vs nerd, cronuts | Wordnik

David Crystal actually did work on the Elizabethan English dialect a few years back for Shakespeare’s Globe in London. He refers to it as the Original Pronunciation of Early Modern English, and he wrote a book about the experience afterward (http://www.pronouncingshakespeare.com/).

I did research into the dialect for a voice and speech class last fall. Crystal’s suggestion for the die/memory conundrum is that both may have ended with /əɪ/, somewhat like a west country dialect. Read his book if you get a chance. It’s very interesting.

Rappers from New York City often use rhymes that don’t really work in many non-New York accents. For example, Biggie’s: “Smoking mad Newports, ’cause I’m due in court for an assault I caught in Bridgeport, New York,” where Newports, court, assault, caught, Bridgeport, and York all have the same /)@/ or /o@/ vowel.

Rhymes that show the speaker keeps “marry” and “merry” separate also jump out when I hear them. For example, Jay-Z’s rhyming “marriage” with “cabbage,” which works because he has a conservative aesch vowel in both words. In the song “Bimmer, Benz or Bentley,” Lloyd Banks does a whole verse mostly rhyming words like “cherry” and “very” with words like “ready” and “heavy.” In most American accents, where the /E/ in the “r” words would be heavily colored by the “r,” these rhymes wouldn’t work. In a traditional New York accent, they do.