People around the world associate Britain with non-rhoticity, the process whereby /r/ is dropped at the end of syllables such as ‘car‘ and ‘start.’ This impression largely stems from the fact that the non-rhotic Received Pronunciation (RP) was the standard for British English for years, and is still treated as such by many foreign language learners. But was RP always “r-less?”

If by “Received Pronunciation” we mean a “standard British accent,” one finds that it wasn’t until fairly late in the game that non-rhoticity was the absolute norm.

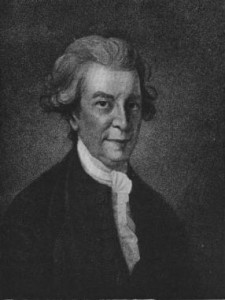

Note, for example, the opinion of renowned 18th-Century language writer, actor, lexicographer, elocutionist, playwright, and education reformer Thomas Sheridan (gotta love those Georgian-era Renaissance men). He stated plainly in his General Dictionary of the English Language (1780) that /r/ “always has the same sound, and is never silent.” Sheridan was Anglo-Irish, which may or may not have skewed his opinion, but my guess is that his thoughts on the matter were not unique. Most accounts describe the 18th-Century as a transition period for non-rhoticity in British English.

In fact, the matter was apparently not settled by the early 1800s. Samuel Johnson collaborator John Walker, writing shortly before Queen Victoria’s birth*, described /r/ in a rather contradictory way:

[R] is never silent … In England, and particularly in London, the r in lard, bard, card, regard, etc. is pronounced so much in the throat as to be little more than the middle or Italian a, lengthened into laad, baad, caad, regaad … if this letter is too forcibly pronounced in Ireland, it is often too feebly sounded in England, and particularly in London, where it is sometimes entirely sunk …

So Walker would seem to advocate maintaining /r/ in these positions, right? Not quite. He sums up this thought with …

… but bar, bard, card, hard, etc. must have it nearly as in London.

So it seems that Walker acknowledged that non-rhoticity was becoming common in England’s “standard” accent, but wasn’t quite willing to admit it.

Of course, by the time Daniel Jones described RP in the Edwardian era, the accent was fully non-rhotic. The question is, what happened between Sheridan and Jones?

The Sheridan quote suggests that at a certain point in 18th-Century, non-rhoticity was viewed as something of a working-class or regional feature, and hence avoided in “polite” speech (to borrow a typical descriptor of the time). There are likely many reasons why RP went from rhotic to non-rhotic; personally, I find that mere population growth is as compelling an explanation as any. London experienced a rapid boom in the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, and many London speech features (such as non-rhoticity) would become unavoidable by the upper orders.

I’m not discussing non-rhoticity in general, of course. The phenomenon itself has a different history from its timeline as a “prestige” feature. But it’s interesting to examine why what once was a regional quirk in eastern England became such a defining marker of “proper” British English.

Much depends on the point at which we decide that RP came into existence. William Gladstone, who was PM for four different terms in the late 19th century, went to Eton College yet his pronunciation gave away that he was from the North of England and his speech was criticised by RP speakers in the early 20th century.

If AJ Ellis’s On Early English Pronunciation can be trusted, a lot of England was still rhotic in the late 19th century. There are some areas where rhoticity may have died out between this work and the Survey of English Dialects (e.g. Yorkshire is mostly rhotic in Ellis but mostly non-rhotic in SED).

That’s a good point, as RP and “Standard British English” need not describe the same accent. I think that non-rhoticity was an important turning point because it would have marked the accent as strikingly different from much of Southern England. That’s also a question appropriate for London generally, but the history of RP and the capitol are certainly intertwined.

I have found a poor-quality recording of Gladstone. It’s difficult to make out the exact pronunciations, but he sounds rhotic to me.

Also, notice the pronunciation of “iron” as [aɪrən]. Gordon Brown was mocked when he said it this way.

Innovations from the London area have for centuries been making their way into the prestige speech of England. One notable recent example is L-vocalization, which within living memory has gone from being a stigmatized “Cockney” feature to absolutely commonplace in RP.

It’s almost more remarkable when a London dialect feature _doesn’t_ make its way into prestige speech within a few generations.

I know that John Wells has included L-vocalisation within RP in his essay, Whatever happened to Received Pronunciation? However, I don’t understand why. It’s still associated with the southern half of the country, and it is quite unusual any further north than Peterborough.

In addition, there has been a habit to attribute features to London too readily, such as with T-glotalling. This was certainly reported for East Anglia and parts of Scotland before it was reported for London.

@Ed:

Could you list/link to contemporary RP speakers who never have L-vocalization? I have a hard time thinking of any.

Here’s an example of Derek Jacobi, using full-on or even affected RP, lapsing into L-vocalization in the word “Iggle-Piggle” http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=o6TBAedCxss#t=193s

I fear that we’re going to disagree on what “contemporary RP” is. It’s usually defined as being non-regional, which is what I had in mind when I wrote the comment above. I’m going to list some people who originate from the north of England whose accents are more-or-less RP, and I don’t think that any of them have L-vocalisation. I’m aware that none of these people is young, but then I don’t think any of them is an speaker of old-fashioned Tony Benn RP either.

Patrick Stewart

Ian McKellen

Jeremy Clarkson

Rowan Atkinson

Rebekah Brooks

Jeremy Paxman

Many of these are Parkinson clips because they come up after one another on the right-hand side of YouTube. Just to be clear, I don’t consider Parkinson to be an RP speaker.

Could his “lapsing” into L-vocalization have something to do with his background? If Wikipedia is to be believed, he’s from Leytonstone, which I think is in East London and his family was working class.

I would argue that the few London features that haven’t become overtly prestigious have become at least covertly so. TH-fronting isn’t part of RP, for instance, but certainly is something of a badge of honor for many people both in London and beyond.

I know little about the history of RP, but I have always thought that the prevalence of non-rhoticity could partly be explained by the fact that the /r/ sound is not the easiest to articulate. I can very well imagine 18th-century youngsters who not only found it chic, but also a lot easier to drop those /r/ sounds.

Can I even trust the accents in the Hornblower TV series to be accurate?

No way, the only boats with not-rhotic crews at that time sailed out of Ipswich. Then sank due to inbreeding.

Pingback: This Week’s Language Blog Roundup: Binders, Britishisms, and more | Wordnik

This discussion on rhotic and non-rhotic varieties of English is very interesting. I began learning English in India from age 5, mostly as a “read & write” language and not as a naturally spoken language. None of our teachers learnt English from native English speakers. Neither did theirs. It would be perhaps four generations ago that anyone would be taught English predominantly by native speakers of English. Theoretically we learnt British English because I still spell neighbour instead of neighbor. But when I immigrated to north America 12 years ago it dawned on me that our English pronunciation was actually a little closer to the north American variety than to the British. We are rhotic, and strongly so with a trilled ‘r’ similar to that of Italian or Spanish. It is easier for us to substitute the glided English ‘r’ for the trill than to totally eliminate the ‘r’.

We tend to pronounce English from the spelling of the word (i.e., vocalization of the written word) approximating English vowels and consonants to those available in our mother tongue. When teaching English, we are taught some exceptions, like “do not pronounce gh” or “pronounce gh like f” and so on and firmly reminded that quite unlike our mother tongue, the correspondence between the written word and its pronunciation is quite weak. Yet teacher and taught continue to vocalize the written word.

The two differences between British English and north American English that immediately strike an average Indian are (1) the rhotic/non-rhotic difference and (2) the way the ‘ay’ sound as in ‘way’ is pronounced on either side of the ‘pond’ – when the Britisher says ‘pay’, the Indian hears it like ‘pie’; north American ‘pay’ is very close to the Indian ‘pay’ 🙂 The maintenance of father-bother vowel difference depends on the region of India. In some states of India the difference is not maintained. In my home state, the difference is maintained. ‘Father’ is ‘fahther’ while the ‘o’ of bother (and the ‘o’ in most other words) is pronounced like the ‘o’ in ‘note’. All different varieties of ‘o’ pronunciatios (like ‘cote’, ‘coat’, ‘cot’ and ‘caught’) are merged into the ‘o’ of ‘note’ which is the one available in the mother tongue.

To me personally, north American English sounds more elegant, perhaps more masculine/adult compared to the British variety which sounds feminine/childish.

I tend to agree with you, Rad. I am a teacher of English born in the Middle-East and raised and educated in Australia since the age of two. As you know, the Australian accent is based on the “British” or South-East English accent, and resembles general RP in its educated form and Cockney in its broad form. Until now, I have never come to terms with this accent, which I still find just tolerable or at worst, very unpleasant. I find aristocratic RP pleasant to listen to, but I cannot convincingly speak like that for fear of sounding ludicrous. The most pleasant accent is the educated General American, which is easy for me to use. I also find non-rhotic accent somewhat effeminate and childish. I have a three-year old son who sometimes pronounces -er as “ah” (e.g. “watah” for water). I constantly correct this accent “error” indirectly by repeating the word with rhoticity at the end. I find myself constantly gravitating towards a rhotic accent.

Pingback: Jane Austen's English | Dialect Blog

Pingback: ‘Later’ as an Accent Marker | Moon Country

“Much depends on the point at which we decide that RP came into existence. William Gladstone, who was PM for four different terms in the late 19th century, went to Eton College yet his pronunciation gave away that he was from the North of England and his speech was criticised by RP speakers in the early 20th century.”

@Ed:

Gladstone indeed went to a public school, but Eton was different in the first half of the nineteeth century. You wouldn’t get a ‘public school accent’ by being a former Eton schoolboy at the time, simply because the school would not shame you into losing it in the first place.

The Public Schools changed radically in this respect after 1870, when the Education Act made them national boarding schools. Upper class and upper middle class pupils started mixing entering these schools and thus mixing with local non-fee paying children.

A few years of social disorders followed and children were separated and eventually these schools turned into full fee-paying boarding schools, were the social climbers could send their children, with the guarantee they would be educated between four walls, sometimes for a whole year, away from home and the bad influence of their local accent.

The public schools changed at the end of century in that peer and teacher’s pressure towards standards (including linguistic standards) was aimed in creating a new chaste: the public school men, with a distinct accent and very useful for the British Empire. When it collapsed, RP lost its prestige with it.

Daniel Jones basically codified their accent in 1909 in his pedagogical manual of pronunciation entitled The Pronunciation of English

The rest, as they say, is history.

Back OT:

About the state of the [r] in England in the 18th century suffice to quote a few phoneticians of the time (the all refer to the sound, of course):

Elphinston (1786): coming from an ‘irritated throat’ and ‘rough, harsh, horrid and grating’

Walker (1791): ‘a jar in the tongue’ and ‘the most imperfect of all consonants’

Buchanan (1762): ‘R, a palatal; it is expressed by a Concussion, or Quivering of

the Extremity of the Tongue, which beating against the Breath as it goes out, produces

this horrid dog-like Sound’

Kenrick (1784): ‘the quibble of Abel Drugger in Ben Johnson’s Alchemist,

respecting the last syllable of his name, serving to shew that our ancestors considered

it in the sense represented by Perius, who calls it litera canina; as bearing a

resemblance to the snarling of a dog.’

(i took the quotes from Charles Jones’s English Pronunciation in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century in case you’re wondering)