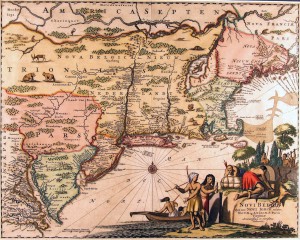

Do place names offer us any insight into the formation of dialects? In a convenient alternate universe, one would be able to make a map of the etymology of place names in America, label which nations or regions these etymologies derive from, and have a perfect visual representation of the spectrum of American dialects. This county could easily be identified as ‘German-influenced,’ that county as ‘Irish influenced.’ Easy, right?

Do place names offer us any insight into the formation of dialects? In a convenient alternate universe, one would be able to make a map of the etymology of place names in America, label which nations or regions these etymologies derive from, and have a perfect visual representation of the spectrum of American dialects. This county could easily be identified as ‘German-influenced,’ that county as ‘Irish influenced.’ Easy, right?

Obviously, such a situation is in the realm of fantasy. One needs only cite French as an example of just how little many American place names correspond to the language spoken there: you’d find no Gallic influence on the local English in St. Louis, Detroit, Coeur-d’Alene, or Des Moines. Some place-namers don’t stick around long enough to have a lasting impact on the local language.

The opposite is also true. There are parts of the country with place names that belie a rich linguistic tradition. Look at maps of the upper Midwest, with generic-sounding towns like ‘Little Falls’ and ‘Alexandria,’ and you find little indication of how recently German and Scandinavian languages were spoken natively by much of the population.

On the Eastern coast of the US, however, this question has some relevance. In New England, accents are often posited to bear a connection to the accents of East Anglia in the UK. And lo and behold, the largest city in the region is named after a small town near the East Coast of England (Boston)*, its county named after an East Anglian county (Suffolk), and the adjacent college town of Cambridge is named after its equally prestigious sister town in the East of England.

And yet these names are exceptional. The colonials of the Massachusetts Bay also had a penchant for naming towns after religious concepts (Salem is related to semitic words for peace like ‘Shalom’ and ‘salaam’); surnames (Quincy, obviously); and English towns that few inhabitants were actually from (as far as I can tell, few if any of the prominent early settlers of Worcester actually had ties to the city’s West Midlands namesake).

It all comes down to when a place is named, who names it, and why they choose that name. Sometimes it reflects the values and background of a real community (as in the ‘Welsh tract‘ of Pennsylvania), while at other times it is chosen by an individual (Portland, OR was given its name based on the decision of a single wealthy businessman from Maine). How useful such names are to linguistic research can only be decided on a case-by-case basis.

*Boston is in Lincolnshire, admittedly, which is not technically East Anglia. However, it is on The Wash, one of the most important bodies of water in Norfolk, and was likely a well known port to 17th-Century East Anglians.

Interesting question.

Here’s a talk I couldn’t go to on Wednesday.

‘Annexing Irish Names to the English Tongue: Language Contact and Aspects of the Anglicisation of Irish Placenames’

This is a topic I had been planning to look into for a long time, and I’m delighted to see that someone is doing it.

Here’s the info I got in the email:

Dr Mícheál Ó Mainnín

Senior lecturer and Director of Research from the Irish & Celtic Studies department

of the QUB School of Modern Languages and

Director of the N.Ireland Place-Names Project (www.placenamesni.org)

(That’s Queen’s University Belfast)

So while I don’t know what he would have spoken about, I have been compiling the odd example without ever doing anything serious. For example Abbey St in Dublin is called Sraid Mainistreach.

As in ‘monastery’ street.

The in the Irish might be evidence of a more open LOT vowel in earlier dialects in Ireland. This realisation remains common in many Irish accents and in American ones too.

No doubt there are zillions more examples and I really want to find more.

So, to respond to your question, it does indeed seem that Placenames can provide evidence of earlier dialects.

I believe Stephen King says in his book SALEM’S LOT that Salem is an abbreviation of JeruSALEM. This has always made sense to me.

I have heard many people say that there are East Anglian influences on Boston speech, but I don’t hear them at all myself.

For what it’s worth, the name for Portland (OR) was determined by a coin flip between two wealthy men. If the coin had landed differently it would have been named Boston.

Native American names are also quite common (as you know) for rivers, and even for many states and counties.

I’m from East Anglia, Norfolk in the Fens near the town of King’s Lynn and I don’t notice an similarities either between my (Broad) Norfolk accent and the (US) Boston one?

Hmm, one could try to make a case for the southwest region/south texas for spanish with chicano english and louisiana for french with cajun english no?

Place-naming is almost always idiosyncratic. Often place-naming is eponymous. For example, New Brunswick, NJ, where I was born, was named in honor of King George I of Braunschweig, Germany, in honor of him and the Hanoverian Dynasty that from the eighteenth century, ruled and still rules Great Britain.

Often, places are named after topographical features, such as Great Falls, among other reasons.

My sister in law and her family are from Boston, and their accents are definitely more east anglian than Northern, yod- dropping, and a FOOT-STRUT split, though she does have a BATH- TRAP merge.

Its a big auld county remember. Northern where it borders with yorkshire, eg Grimsby, and east anglian where it borders across the Wash.

Being brought up in Northampton, where the older inhabitants show east anglian sounds in their accent, some of which I have myself, like monophthong SQUARE and NEAR vowels, (the classic Northampton phrase, is “awroit, me duck, gooin dayn the maakit on Toozdi? [hello, my dear friend, will you be going to the market square on the day after monday?]), the classic New England “paak the caah in Haavud Yaahd” sounds very familiar.

But lets face it, we all have melting pot accents nowadays – though there must be some reason why the archetype new englander is non rhotic, but the virginian and carolinian isnt.

Maybe more useful to look at trends in placenames, rather than individual. Though I will always be struck how, when researching New England that a tiny, one street, no shops, single daily bus service place like Sturmer in Suffolk should have a twin in NE America.

Pingback: This Week’s Language Blog Roundup | Wordnik

Hello, Neat post. There is an issue together with

your web site in web explorer, might test this? IE nonetheless is the market chief

and a large section of other people will pass over your magnificent writing due to

this problem.