[Ed. note: An earlier version of this post had an embedded sound clip of Philip Shaw reading a letter by Richard III in a historically accurate accent. Unfortunately, I’ve had a few embedding issues since updating to the latest version of WordPress, so for now, click on the link four paragraphs below this one to hear the relevant interview.

[Ed. note: An earlier version of this post had an embedded sound clip of Philip Shaw reading a letter by Richard III in a historically accurate accent. Unfortunately, I’ve had a few embedding issues since updating to the latest version of WordPress, so for now, click on the link four paragraphs below this one to hear the relevant interview.

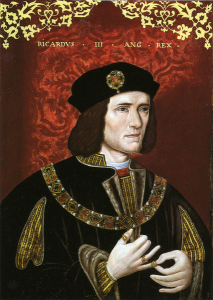

Experts confirmed this week that a body found under a Leicester parking lot/car park belongs to Richard III. It’s an exciting discovery and a crucial step in establishing the differences between the historical king and Shakespeare’s less-than-flattering portrait.

Accent enthusiasts may be puzzled, however, by a series of news stories about RIII’s “Brummie Accent.” Most quote University of Leicester professor Philip Shaw, who has this to say on the matter:

Unlike today, individuals were more likely to spell words in ways that reflected their local dialect. Therefore, by looking at Richard’s writing, I was able to pinpoint spellings that may provide some clues to his accent.

To be clear, though, Richard III did not have anything remotely resembling a contemporary Brummie accent. Nor is Shaw suggesting this. Listen to this wonderful interview, in which he gives us an idea of how the king would have spoken.

Needless to say, this is hardly classic “Brummie,” as headlines suggest. We’re talking about the earliest stages of the Great Vowel Shift, when the language would have sounded foreign to most contemporary ears.

Whatever marked a West Midlands accent at the time would not necessarily have been what marks that accent now. Brummie today is noted for its lack of several distinctions common in England’s South (the FOOT-STRUT and TRAP-BATH splits) and a number of vowels which somewhat resemble strong, vernacular Cockney (i.e. the long trajectory of the diphthongs in KITE, GOAT, and FACE). It’s unlikely any of these features would have been sociolinguistic markers in the 15th-Century.

We are accustomed to seeing films about Henry VIII or Richard III in which everyone speaks the Queen’s English, but it bears repeating that this is a dramatic convention divorced from reality. It is doubtful contemporary Standard English-speaking time-travellers would be able to easily understand their own language until at least Shakespeare’s time. So needless to say, “Brummie” means something very different here!

This is not my specialty, but it just sounds like Middle English to me. Are there any features that are specific to the West Midlands in his dialect?

I’m not sure about what makes it particularly Brummie, although Shaw says something about “will” sounding like “wule.” It is, believe it or not, a very early form of Modern English. It sounds more like Middle English, though, because the vowels in MOUTH and KITE are very close to the vowels that many contemporary accents have in GOOSE and FLEECE. That is, it’s a very slight diphthong.

Oh whoops

I knew that theatrical convention in English tended to use formality of speech as well as older forms to suggest history (because it is usually the more formal documents that are preserved, and their pronunciation is often associated with formal occasions), I didn’t think much about the vowels. Early Modern forms have the double support of both Shakespeare and the Authorised Version, but actors don’t even attempt to replicate thoses vowel sounds. For that, because it is impression and not reality of ancient speech that matters, they use the vowel sounds of a prestige dialect, or from their great-grandfather’s day.

Note that Tolkien – who could easily have done otherwise if he chose – was explicit in telling us that his characters did not speak any kind of English, but that he was using various conventions (including eye-dialect) to evoke what was being said in one of his invented languages. Or so he said. Personally, I think Sam really did talk that way.

In the interview, he suggests that the dialect could be either West Midlands or London. That’s a very broad guess.

When Richard III lived, Birmingham would have had a population of around a thousand. I don’t think that a recognisable Brummie accent came to exist until it became a big city in the 20th century.