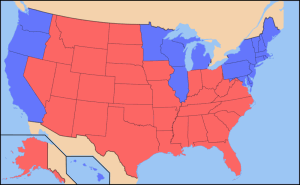

In a brief piece in Time this week, famed linguist William Labov suggested that American dialects are getting more distinct rather than less. The article is extremely short, but I was nevertheless intrigued by Labov’s comment on the connection between accents and the Blue State/Red State divide:

It’s not entirely clear why accents are growing stronger, but Labov says that the sound differences are increasingly being exaggerated. His other explanation is that “…dialect differences have become associated with political differences, so that the Blue States/Red States division comes close to the boundary between the Northern and Midland dialects.

For the few readers who missed the “Red State/Blue State” phenomenon, Red and Blue refer to mostly conservative US states (Red) and mostly liberal US states (Blue). The divide slightly corresponds to the American North and South, although that paints an overly simplistic picture.

The idea that political differences create dialect differences is nothing new. In fact, more than one linguist has suggested that what we think of as the “American Southern” accent emerged as a result of the political divide created by the Civil War. Here linguist Edgar W. Schneider summarizes the work of sociolinguist Guy Bailey*:

Essentially, Bailey’s claim is that Southern English was shaped not by retentions of British dialect features but by late nineteenth-century innovations, that is, linguistic developments of the post-Civil War, “Reconstruction” period, when Southerners used distinct dialect features to express their regional identity threatened by the presence of large numbers of “Yankees.”

Is something similar happening within the context of America’s contemporary political landscape?

I’m betting Labov’s quote in the Time article is out of context (note that he isn’t really offering an “explanation”). That being said, the Red State/Blue State divide doesn’t strike me as linguistically dramatic as the Red/Blue divide between dialects within regions of the country. Take Texas for example. Austin, Dallas and Houston all voted Democrat in the last presidential election**, and all three cities are developing markedly less “Southern” varieties of English than those found in the rest of the state.

But I can’t say for sure if the gulf between American Liberal and Conservative politics is resulting in an equally large linguistic gulf. Have political differences really increased our dialect differences?

*Schneider, E. (2003). Shakespeare in the coves and hollows? Toward a history of Southern English. In S. J. Nagle & S. L. Sanders (Eds.), English in the Southern United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

*Their counties did, at least.

I wonder if education level and economic class have something to do with this.

While Labov’s contention that regional dialects are becoming stronger, I doubt that political conditions are the reason. The Republicans gained strong majorities in the formerly-Democrat voting south after Lyndon Johnson;s Civil Rights legislation in the sixties, but there are still plenty of Democrats south of the Mason-Dixon line – do they also have stronger accents? I think that southern conservatives may be emphasizing their accents as a factor in identity politics – George Bush, born in Connecticutt, educated at prep school, Yale and Harvard in New England, spoke with a marked Texas accent. Perry, of course, does the same.

I think you meant “voted Democrat”, as *all* US states (maybe except Palm Beach County, Florida 🙂 ) voted democratically in that election

@Charles,

Economics and class are definitely the biggest factor outside of geography. I was born and spent my early childhood in Louisville, KY, and the dialect differences between the wealthy and poor areas of that region are remarkable.

@Marc,

Of course, accent exaggeration isn’t an exclusively conservative tactic. Obama gets a bit of a twang when he visits Kansas.

@E.C.

Thanks for point it out! I hate that our political parties have been given the arbitrary names “Democrat” and “Republican.” It’s almost as silly as if they were named the “Freedom” and “Liberty” parties.

What about the black populations in red states, especially in the South? There is a perception at least that most in that population group tend to vote Democratic.

True, although that group is somewhat linguistically separated from other Southern Englishes. But as a group they certainly tend to vote with the Democrats more than the South as a whole.

Related to this, can anyone support or refute my conjecture that the Northern Cities Shift is at least in part a result of the migration of Southern and Appalachian whites to Northern cities during and after WWII and is driven by a desire on the part of “native” whites to sound as little like “those people” as possible?

That one’s new to me. I’m inclined to disagree, because I’m unclear as to what features of the NCS indicate some kind of Appalachian hypercorrection. Possibly the centering of KIT and DRESS, or maybe the backing of STRUT. But those are typically thought to be the last stages of the shift, not the first.

Thanks. Another fascinating conjecture collides with the facts. What did we do before language blogs? (Answer: went around repeating the kind of unfounded conjectures that still abound among people that never read language blogs.)