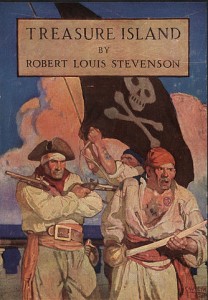

I recently read Stevenson’s Treasure Island, a story I greatly enjoy as a child. The novel’s pirates speak with a dialect I find puzzling as an adult reader: is it the West Country of the early chapters’ setting (akin to the famed “pirate dialect”)? Are some of the pirates Irish? Is some American English thrown in the mix?

Stevenson was not entirely going for accuracy. The story is so associated with the era of wigs and tri-corner hats that it’s easy to forget the book was written in the late Victorian era, and likely doesn’t reflect the speech of 18th-Century seamen with total verisimilitude. Stevenson wrote about a largely fanciful world, generally speaking. Many adaptations of the film are set in tropical climes, for instance, but the pines, grey trees, and sweltering heat that the author describes suggest a curious mashup of different locales.[1]

I find myself especially curious about the occasional Americanisms which pepper the pirates’ speech. For instance, Long John Silver uses the phrase let her rip, a term we still use in America today and seems to be of American origin. Does US English share this phrase with rural British English, or did Stevenson picked it up during a sojourn in America? He married a native of Indianapolis, after all.

The question is especially complex when young Jim Hawkins speaks of having “the blues:”

If we had been allowed to sit idle, we should all have fallen in the blues but Captain Smollett was never the man for that. All hands were called up before him, and he divided us into watches.

We tend to associate the blues with a very American musical form, but the term’s roots on this side of the Ocean are dubious.[2] A Google Books search yields a fair number of examples similar to Stevenson’s in British Victorian literature, in fact, such as this passage from an obscure tome titled Violet Rivers, by Winifred Taylor:

“I only wish there were an end to all these books, for they’re nothing but weariness of the flesh to me.” And Harry put his hands in his pockets, and gave a great yawn, as if to convince his hearers that he was speaking the truth.

“There’s no use going into the blues over them,” spoke Cecil again. “What can’t be cured must be endured, you know.”

As in the above two passages, many examples I found from the 19th-Century used the construction “in the blues,” or opted for a related adjective like “into.” But the meaning is nonetheless similar to how we treat the word in contemporary English. The term appears similarly in American texts from the period, however. So whether Stevenson picked up the term among Englishman or Americans is anyone’s guess.

Yeah, the possible American flavoring in TREASURE ISLAND is intriguing. It’s important to remember, after all, that piracy and Britain’s North American colonies were closely intertwined. Captain Kidd, for example, lived in New York. Blackbeard famously blockaded Charleston, South Carolina, and , after receiving a pardon, lived for a time in Bath, North Carolina. And, of course, Blackbeard was killed by forces sent by the Royal governor of Virginia in Ocracoke, NC. Bearing Blackbeard in mind, it’s interesting to note that Stevenson has Captain Flint die in Savannah, Georgia……

A very interesting insight into the earlier origins of

Words and expressions. English vernaculars travelled to America with the early colonists

And the transported slaves from Africa had very diverse language histories, so Acquired English provided the communication tools for interaction and self expression. Their circumstances of enslavement and general abused of their human rights found expression in the blues

Another interesting American connection to TREASURE ISLAND is that Stevenson was influenced by Poe’s “The Gold-Bug” (which concerns the breaking of a code in order to find Captain Kidd’s buried treasure) in his writing of the tale. As Stevenson himself remarked, “I broke into the gallery of Mr. Poe… No doubt the skeleton [in my novel] is conveyed from Poe.”

The OED is your friend:

Blue – 12. the blues (for ‘blue devils’): depression of spirits, despondency. colloq.

1741 D. Garrick Let. 11 July (1963) I. 26, I am far from being quite well, tho not troubled wth ye Blews as I have been. 1807 W. Irving Salmag. (1824) 96 In a fit of the blues. 1856 G. J. Whyte-Melville K. Coventry viii. 89 The moat alone is enough to give one the ‘blues’. 1883 Harper’s Mag. Dec. 55 Come to me when you have the blues. 1887 ‘J. S. Winter’ That Imp ii. 11, I wonder you and Betty don’t die of the blues. 1960 New Statesman 27 Feb. 274/2 The post-election blues are beginning.

“Blue devils” first appears in anything searchable with Google Books in 1719.

According to this article (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/debra-devi/blues-music-history_b_2399330.html), the term “blue devils” originated in 17th-century England to refer to “the intense visual hallucinations that can accompany severe alcohol withdrawal.” Eventually, it was shortened to “the blues,” and “blue” became slang for “drunk” in the 18th century.

I guess THAT’S why they call it the blues, Elton.

…or perhaps it’s this, from Wikipedia: “[I]t derived from mysticism involving blue indigo, which was used by many West African cultures in death and mourning ceremonies where all the mourner’s garments would have been dyed blue to indicate suffering.” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blues)

Per the “blues” – I strongly suspect that it is more of nautical origin rather than country – if you’ve ever read Patrick O’Brian’s novels you would surmise that ‘getting the blues’ is more a direct reference to blue devils, which actually spoke more of the “let down” after battle that a naval warrior experienced…ie, when the adrenaline from activity in battle dissipates. I would imagine that because there was a lot of interchange between countries on naval vessels, well past the Napoleonic wars and the war of 1812, that the phrase was used by both British and American sailors.