A metonym is a word which symbolizes another word with which it has some relationship. (Not the most elegant definition, I know). A good example is the way we substitute geographical locations for authority figures or bodies of Government. We use Capitol Hill for the US Congress; Downing Street for the British Cabinet; and of course, the White House for the US presidency.

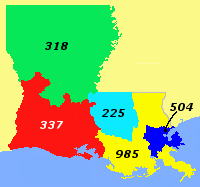

There’s a unique type of metonym that has emerged within the past few decades whereby a US city’s area code comes to symbolize the city itself. You often hear this in Hip Hop: the New Orleanian Lil’ Wayne boasts of being ‘live from the 504,’ while there is an East St. Louis rapper who goes simply by Mr. 618. And Seattle MC Macklemore pokes gentle fun at the convention in his track The Town (Seattle is 206 territory):

Now when I say 2-0 … nah, you know the rest …

This is our music, our movement, the history lives through us.

(He seems to suggest that his love for his hometown can’t be reduced to a standard Hip Hop trope.)

What I find brilliant about area code metonymy is the way it’s recognizable by residents yet baffling to outsiders. For instance, a Philadelphian probably sees the digits ‘215’ twenty times a day, while the rest of the nation is oblivious to this detail of the city’s culture.

I believe this is an example of how cities have both ‘dialects’ and ‘registers.’ There is overlap between the two, but they’re not quite the same thing. A ‘register’ (I’m going off Peter Trudgill‘s definition) is both a kind of jargon and a way of indicating one’s belonging to a group. Just as physicists and Star Trek aficionados have registers*, so do those who claim ‘membership’ to a city.

Another example of such lingo can be seen in neighborhood names. How you use them in conversation is a way of displaying your value as an urbanite. Not only your knowledge of a particular neighborhoods’ existence (if you claim to be an Angeleno, you’d better be aware of a neighborhood called Los Feliz); but also your ability to demonstrate understanding of that neighborhood’s cultural nuances. This is why New Yorkers roll their eyes at a New York Times piece about Brooklyn as if it’s next hip nabe (because Brooklyn is not a neighborhood and this isn’t 1986). Some Grey Lady scribes don’t quite grasp the register of their employers’ namesake.

Other ways urban registers manifest themselves are through mass transit terminology (El, MAX, Muni, BART, MTA), the names of bars and restaurants, names of suburbs, foreign loan words, highways (Atlanta’s ‘outside the perimeter’), political boundaries (LA’s ‘behind the Orange curtain’), industries, weather (Seattle’s ‘the mountain’s out’), and many other terms both abstract and concrete.

To reiterate, though: this doesn’t constitute the dialect of a city. An ardent newcomer can speak the register as fluently as a native (not to mention that there are really many registers depending on the community within a city which you most closely identify with). But I find it fascinating how the two mingle and overlap.

*Um, I’m not saying they’re the same group.

A nice example of area-code metonymy is De La Soul’s “Area” from their 1993 album Buhloone Mindstate.

I like how the area codes in those lyrics are allowed a degree of semantic and syntactic flexibility. For instance, they can easily take a definite article (‘the 516’) and can be pluralized (‘the 301s’). There are some unusual English place names that can do both (like ‘The Woodlands, TX’) but you can’t have, for example New York, *The New York and *New Yorks refer to the same city!

I will just mention a couple others i’ve seen on bumper stickers:

– airport codes: i’ve seen PDX and YYZ

– athletic competition lengths: 26.2, 13.1, 50 (?)

Ooh, yeah. PDX got especially huge, almost more, I might argue, than any other airport code metonym. Possibly because it has a kind of anapestic elegance: ‘pee-dee-EX’ is more fun to say than something as awkward as ‘jay-eff-kay.’

I was going to wonder if LAX was one of them, but I can’t recall off the top of my head any occasions when I’ve heard it used to refer to the entire area.

I think LAX is blocked somewhat by the more established, and succinct, LA. Although if you were to pronounce it as a word, it would make for some great puns given the city’s laid-back reputation (“This town is totally LAX”).

Perhaps this is wishful thinking (as I am one of many Atlantans who would like “Hotlanta” to go away — perhaps it is part of the everywhere-but-Atlanta register?) but I’d pit ATL against PDX.

I’ve also seen airport codes used a lot on twitter as a shorthand for larger cities, at least in Canada. Toronto is yyz, Edmonto is yeg, Vancouver is yvr, etc., even when the airports aren’t necessarily in the city. It’s not used for every city, though. Hamilton and London Ontario, for example, are HamOnt and LdnOnt rather than yhm and yxu.

one of the first times I heard the area code used in a way to symboilize an area was in Pulp Fiction, when Samuel Jackson’s character stated he ‘didn’t have any friends in the 818’ after John Travolta’s character mistakenly killed their passenger. I had to look up where 818 was because the terminology interested me.

For a relatively brief while in the 90s we had area code snobbery in London – Inner London was 071, outer London 081 (basically anywhere 081 was the suburbs – and therefore distinctly uncool) . Now we have the same code everywhere I’ve noticed that snobbery has reverted to public transport zones (zone 3 and beyond replacing 081 as the suburbs for many)

The same thing happened in New York. When I went to college there in the late-90s you still heard Manhattanites say they “don’t do the boroughs.” But now that movie stars live in Brooklyn and Food & Wine articles gush over the cuisine of Queens, the phrase makes one a target of snobbery rather than the opposite.

What is the difference between dialect and register?

A register is a type of language particular to a certain social, vocational, or professional context. That can mean degrees of formality, sports jargon, professional terminologies or (in the way I’m using it here) a vocabulary shared by those who affiliate themselves with a particular city.

Beyond this, I find that when people talk of ‘registers’ vs. ‘dialects,’ the latter involves the deeper structures of language. A register can involve a unique lexicon, but in my mind it can’t have salient syntactic features the way a dialect does. A register can even have some phonetic attributes (for instance, the way the ‘informal register’ will often say ‘goin’ rather than ‘going’), but doesn’t involve phonological structure.

What’s a lexicon, a salient syntactical feature, a phonetic attribute, and a phonological structure? In English for us non-specialists, please.

Sorry, wrote that response WAY too late at night. A ‘lexicon’ is basically your mental dictionary. The point I’m making above is that ‘registers’ tend to deal more with vocabulary and maybe some very superficial aspects of pronunciation.

Let’s take, for instance, a science professor giving a lecture at a conference. He’s probably going to use a lot of terminology specific to his field (e.g. ‘meson’), and may also change his pronunciation slightly given the academic setting (e.g. he might aspirate his t’s a bit more at the end of words). But in order to shift to this register, he’s unlikely to change the syntactic structure of his everyday language (e.g. he won’t say ‘these mesons be made of quarks’), nor would he drastically alter the phonological structure of his language (by say, going from a rhotic accent to non-).

A humorous illustration of this principle can be found in Season 6 of Friends. Ross starts a teaching assignment and gets so nervous he starts speaking in a faux-British accent. Attempting to speak in an academic register, he overshoots things and starts speaking a different dialect.

I grew up with an area code of 416 in Southern Ontario. When I was around 10, our area code changed to 905, with the 416 area code being restricted to Toronto. 416 is now a nickname for Toronto, while “The 905” is a nickname for the municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area outside of Toronto itself, although there is a small handful of places that have a 905 area code but aren’t part of The 905. This usage might have hip hop origins, but I rarely see it used in a hip hop context.

Maestro had a track about 15 years ago called “416/905” but I don’t know of any other examples.

I was going to say something similar about Montreal – the suburban areas immediately surrounding the main city of Montreal use the 450 area code rather than the 514 area code that the city of Montreal has. And people have been known to refer to things as ‘sooooo 450’ etc.

That Macklemore song made me so homesick when I was living in NYC .

Also the Blue Scholars “North by Northwest” “… suffering from acute Two-Oh Sickness”