A commonly held assumption is that New England accents are cousins of East Anglian accents in the UK. It’s an impression shared even by non-linguists, as this interview with British actor Tom Wilkinson from some years back attests (he discussed hanging out with Maine locals while shooting In the Bedroom):

A commonly held assumption is that New England accents are cousins of East Anglian accents in the UK. It’s an impression shared even by non-linguists, as this interview with British actor Tom Wilkinson from some years back attests (he discussed hanging out with Maine locals while shooting In the Bedroom):

“The accent they have, the broad Maine accent, is much closer to an English — it’s like a brother to the Norfolk accent. Those guys could walk into somewhere in East Anglia and people would think they were local.”

So is there a clear connection between the two?

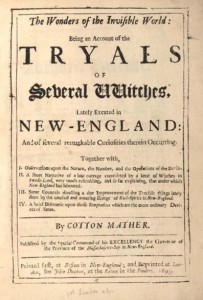

The reason for the supposed similarity is that many of the original New England settlers reportedly hailed from East Anglia. I can’t comment on this claim; my knowledge of historical demographics of this sort is hardly robust. I would note, though, that when I researched the Salem Witch Trials in high school, the ancestries of its participants struck me as more diverse than that. Many bold-faced names in Salem had family from London, Lancashire, Derbyshire, Somerset, Norfolk, and any number of other places.

It is certainly true that both a New Englander and an East Anglia might utter the classic phrase ‘Park your car in Harvard Yard’ similarly: with a centralized or fronted [a] sound that might give the impression that ‘park’ is pronounced like ‘pack.’ This feature is shared by many other accents, of course, so this alone doesn’t immediately invite comparison.

Likewise, both East Anglia (well, most of it) and Eastern New England are non-rhotic, meaning the /r/ is dropped at the end of words like ‘car’ and ‘better.’ Again, not a very compelling piece of evidence.

Like a lot of trans-Atlantic comparisons, this one seems to work best when you’re comparing rural, isolated accents and not metropolitan ones. If you compare a Bostonian to someone from Norwich, you’re unlikely to find much common ground. But listen to this Maine Lobsterman from the far East of the state, and I can see how Wilkinson’s statement makes some sense:

Then compare this to an old (and possibly not entirely authentic) recording of a man from Norfolk:

See any similarities? I like to exercise caution with claims like these, since so much has changed about the English language since the time of the Massachusetts Bay colony. I defer to anyone who knows a bit more about early American immigration patterns.

“See any similarities?”

They’re both varieties of English. Other than that not really. The problem with claims like this is that even if the modern accents sounded vaguely similar, you still wouldn’t know what both accents would’ve sounded like in the 17th century.

I would note at least one place where the two accents are entirely contradictory. East Anglian accents appear to consistently have a fronted MOUTH vowel: the Survey of English Dialects, mentions variants such as [ɛʊ], [ɛʉ] or [æʉ]. This is quite the opposite in New England, where MOUTH is strikingly back throughout the region: [ɑʊ].

Your right: English in general has changed so much since the 17th-Century, that even if the two accents may have once been related, you can only spot a few small similarities, which both share with any number of other accents.

As you do so often, you have written an article I have wanted to write for years (probably better than I would have done, quite apart from the fact that I never actually sit down to write anything unless absolutely forced to). Thank you for skewering yet another careless assumption about accent and dialect.

For what it’s worth, here are some links to indisputably authentic Norfolk (England) accents from speakers born in the 19th century:

http://sounds.bl.uk/View.aspx?item=021M-C0908X0059XX-0900V1.xml

http://sounds.bl.uk/View.aspx?item=021M-C0908X0060XX-0101V1.xml

http://sounds.bl.uk/View.aspx?item=021M-C1315X0001XX-0629V0.xml

These represent only a small sample of the riches available through the British Library.

Jim is right of course – we still can’t know for sure how anybody sounded in the 17th century, though some researchers have been able to come up with some plausible theories based on such evidence as they could uncover and interpret. In the end, though, educated guesses are still guesses.

Thanks, Amy! One thing I find interesting about the British Library (i.e. SED) recording for Norfolk is that many speakers exhibit a CLOTH-LOT distinction not similar to some types of American English (i.e. ‘lot’ is [ɑ] while ‘cloth’ is [ɔ:]). American as this may seem, the split is NOT a part of much of Eastern New England speech. I can see how one can pick up on a vaguely ‘American’ quality, but I agree with Jim as well: you would have to account for centuries of accent evolution to pinpoint the influence to New England.

I’m surprised that no-one has mentioned BATH-broadening, of which there is some evidence from East Anglia in the 17th century, early enough to have been carried to New England by the earliest settlers.

The old-fashioned Boston accent also features BATH-broadening, which is usually ascribed, along with R-dropping, to a kind of 19th-century Anglophilia. But I wonder what evidence there is of its possible existence in New England during the colonial and antebellum eras.

Wells, meanwhile, ascribes the old-fashioned “New England short O” to East Anglian influence.

Here‘s a Google Books link to the Wells “short O” discussion.

You can still hear BATH-broadening today in some words with older New England speakers (and almost universally in aunt I think). Listen to Roger say half at 16:36 into this clip.

But yeah, maybe BATH-broadening happened in East Anglia before it happened anywhere else in England. Maybe the same is true of R-dropping. I feel like I’ve read something about this somewhere.

I’m pretty sure that r-dropping occurred in East Anglia before elsewhere, at least in Southern England. That’s not a particularly controversial observation: This map, taken from the SED and Wells, gives a good idea of where rhoticity would have occurred around the turn of the 20th-Century. East Anglia and Greater London would have been the only areas of Southern England that were firmly non-rhotic (depending on what one’s definition of Southern England).

Although in the case of R-dropping,

* I think it’s too late to have affected the original New England settlers

* there’s some evidence that it was a relatively recent (mid-late 19th century) phenomenon in New England, which reached its peak around the 1930s.

Off-topic here, but when I listen to the Maine fisherman video, there are a few spots where I’m reminded of the accents of some maritime Canadians.

Parts of eastern Canada were settled by New Englanders

RE: the East Anglia origins of many parts of New England,

David Hackett Fischer’s ALBION’S SEED is a terrific study on the British regional origins of Anglo America.

Thank you for an interesting article. Part of my family is from New England, and in doing their genealogy over the last several years I have noticed that it is not as overwhelmingly East Anglian as I had expected. Particularly noteworthy is the significant population of Ulster Plantation Lowland Scots in New Hampshire and Maine. In my line there are also a couple of (apparently Highland) Scots who were defeated in battle with the English and sent off as indentured servants to New England.

I think about this day and night.

I supervise costumed interpreters at a Boston historic site and I’ve been trying to find any scrap of evidence of what the authentic 18th century American accent would sound like for years. What I’ve learned is that while East Anglians were the largest group to come to NE, they were not a huge majority. Instead, as you identified, the immigrants were diverse (though, they were overwhelmingly English.)

In a group of mixed accents, it’s been shown that regionalisms tend to neutralize, so it’s probable that 18th century New Englanders would have spoken a difficult to locate dialect. A few English travelers commented that their English was surprisingly uniform and “proper” compared to the variety of the mother-country.

My quest continues.

Some colonial words have survived from the 18th century. In Maine, you will hear some of the older generation say the word “Ayuh.” Abigail Adams of 18th century Braintree/Quincy used that word frequently. It means “yes.”