I’ve used the term Estuary English quite a bit on this site. For the dialect novices out there, I’d like to explain what this phrase means, and my personal take on it.

I’ve used the term Estuary English quite a bit on this site. For the dialect novices out there, I’d like to explain what this phrase means, and my personal take on it.

Estuary English is a hard concept to define. Sometimes it’s referred to as a contemporary “standard British accent;” other times as something more regional. So before I go further, let’s look at the original definition of Estuary English, proposed by linguist David Rosewarne in 1984:

“Estuary English” is a variety of modified regional speech. It is a mixture of non-regional and local south-eastern English pronunciation and intonation. If one imagines a continuum with RP and London speech at either end, “Estuary English” speakers are to be found grouped in the middle ground.

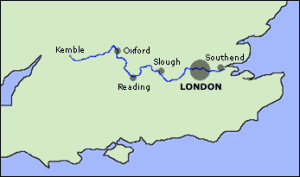

The heartland of this variety lies by the banks of the Thames and its estuary, but it seems to be the most influential accent in the south-east of England.

As Rosewarne and other linguists suggest, Estuary is a type of accent found in Southeast England. Notably, it is found in parts of the region beyond London itself: Essex, Sussex, Kent, Berkshire, and such.

For an example of Estuary, I often use comedian Ricky Gervais, whom I would consider an Estuary speaker, from Reading:

It is hard to pinpoint what Estuary is, but linguists tend to mark it by a number of features:

–T-Glottaling: The ‘t’ in a phrase like “lot of” becomes a glottal stop [ʔ] (“lo’ of”); this may occur in words like “butter” as well (although this point has been debated a good deal).

–L-vocalization: The ‘l’ in words like “bell” becomes a vowel sound (“bew”).

–The London Vowel Shift: Estuary participates in a vowel shift typical of London, whereby the vowel in FACE moves toward the vowel in PRICE (hence “lace” moves toward “lice”); the vowel in PRICE moves toward the vowel in CHOICE (so “buy” moves toward “boy”); not to mention several other shifts too numerous to mention here. (You can see a more detailed description of Estuary’s phonetics in this John C. Wells article.)

A valid objection to the concept of “Estuary” is that many of these features existed throughout Southeast England long before contemporary times. In other words, these were never exclusively “London” features, and many of the areas where “Estuary” has been observed have had similar accents for at least a century.

But that’s not the point of the Estuary distinction. At least not in my opinion. What makes the accent interesting is that people who in previous generations would have spoken Received Pronunciation or perhaps near-RP (standard British English) have instead opted for this more “regional sounding” accent. Estuary isn’t radical because of its spread; it’s radical because of the type of people who speak it: middle-class young people, celebrities, and white collar professionals.

Estuary is also perceived, by some, as a phenomenon moving throughout the UK (not just the Southeast). This is a problematic notion, since many features of London English coincide with those of other accents: a similar vowel shift to London’s can be found in the Midlands, and t-glottalling is a traditional feature of accents as disparate as those in Manchester, Scotland and Dublin.

One feature that is almost inarguably spreading, however, is l-vocalization.* However, given that this feature has become fairly standard in genteel accents (I often use Tony Blair as an example), is this indicative of the spread of Estuary? (Whatever that means). Or is l-vocalization becoming something of a prestige feature?

As Estuary English is a very abstract concept, I have a hard time answering these questions. I think there are features spreading rapidly throughout the UK that indeed seem to gravitate from Greater London. Given that the region now accounts for a good 20% of the UK’s population, this is not very surprising. But can these trends specifically be attributed to “Estuary?”

NOTE: I removed a video clip from this post in a later revision (although it’s referenced in the comments). It’s authenticity was debatable, and as it didn’t really add anything to the discussion, I took it out completely.

There are no “l” vocalisations in the northern guy’s speech, as the term is understood in the UK. Even final ´l´is a tap in “as well” and “a(b)le to”.

I’ve never heard “l” vocalisation further north than Peterborough personally.

I agree with you: I don’t hear clear evidence of L-vocalization from that speaker.

Having said that, there is ´l´deletion when he says ´school´, though he is making the tongue movement for l, he’s stopped the air before it sounds. This is a different feature though, not especially related to estuary, which has a lip movement replacing the ´l´.

I have to admit that that “school” is what I based my assumption on. But you’re right, there’s not much evidence outside of that. Anyway, I think I’m going to revise this post to get rid of that clip: you can find better evidence elsewhere!

According to what I’ve read, l-vocalization is one of the features that hasn’t spread to the North (yet?), unlike t-glottaling and th-fronting which definitely have.

t-glottaling has always existed in the North, or certainly since at least the ’60s, when estuary English was still forming (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aP9J5akyKTQ, here’s Fred Trueman talking about 1970, lots of glottals, despite the formal setting).

The classic “t’shop” representations of northern English are attempts to represent the glottal which represents “the” in most of Yorkshire, and replaces “t”, while “d” is replaced with “t”.

It’s also used as one of the traditional dividing lines between Manchester and Liverpool English, the former t-glottaling, the latter more typically using t-spirantization. (I’m always amazed, as an American, how two cities that close to one another can have such different accents.)

I think the closest the states gets to geographical accent difference is with philadelphia and new york at ~95 miles. Liverpool and manchester being ~35 miles, which is amazing for just 35 miles from an american perspective

Also, woah spirantization.

There is one possible North American analogy, the international divide between Detroit and Windsor, ON. But even then, there’s at least a body of water (and an international border) in the way.

Even more surprising to you might be the fact that there is a clear transitional zone, which has accents that are mixtures between Scouse, Manc and the traditional Lancashire accents further north. After living in the area myself, I can certainly differentiate between Wigan, St Helens, Skelmersdale and Warrington accents.

What distinguishes Estuary and Cockney from other accents is T-glottalling in intervocalic position. I don’t hear that in most Northern accents: certainly not in the YouTube of Fred Trueman that you linked: he clearly has alveolar /t/ in “water” and “Rotterdam”.

I live in Leeds now, and t-glottaling in most positions in now very common amongst young people. You can tell that this is a recent feature though, as the older generation hardly use it at all. I think that kids see it as a cool thing to do.

However, there is an older feature of Northern speech whereby a T is replaced by an R in phrases such as “gerroff” and “shurrup”, so this might have laid the ground for T-glottaling. John Wells spoke of it here. http://phonetic-blog.blogspot.com/2010/12/t-to-r.html

I think that you should be wary of ideas that RP used to be more dominant. The media were not as pervasive back then. I can think of two examples of politicians whose speech was not up to RP: Stanley Baldwin, who led the Tory Party for much of the early 20th century, had a strange accent, which gave me the impression that he was trying too hard to sound posh; Enoch Powell, a Tory Minister during the 1960s, had a mild West Midlands accent and, for all he was hated, nobody seems to have hated him for his accent.

re. t-glottalising, intervocalically. I suspect it is more common in northern accents now than in the 1960’s. But it was already happening in the ’80s, and indeed, was near universal among my generation who were at primary school then. To say that a feature originating at that time is due to estuary influence is ridiculous, we simply didn’t hear any estuary then, as it wasn’t on the media any more than our own accents were (less in fact). I suspect intervocalic glottalising started as a badge of working class identification which has extended from various starting points, London, Yorkshire, the Central Belt of Scotland, and South Wales.

According to J. C. Wells there is no such possibility as ‘t-glottaling’ in the word ‘butter’ as ‘t-glottaling’ in Estuary is not intervocalic, whereas it is in Cockney…

Actually I think, according to Wells, that /t/ can be a glottal stop intervocalically (if that’s a word) across word boundaries in Estuary and in modern R.P., e.g., in get off or lot of. But It just can’t be intervocalic within a single word in either accent. That would be Cockney.

Although as a commenter noted some time back, even Wells himself has suggested these earlier markers may now be out of date.

I didn’t see that comment as I’m fairly new here. Where did Wells write that? In the linked article or somewhere else? I have to admit that I’m not an expert on these varieties (I’m not even English, in fact), but everything I’ve read says that both Estuary English and contemporary R.P. can have a glottal stop in, e.g., quite interesting, but that only Cockney can have it in butter. Are you saying that Wells has written that contemporary R.P. can also have it in butter (which would be very surprising indeed) or just Estuary English? And if this isn’t a difference between E.E. and Cockney anymore, then what is the difference between the two varieties? I would think it would only be one of grammar, e.g., he weren’t scared of anyone (Cockney) vs. he wasn’t scared of anyone (Estuary English). Or is it a difference of frequency, e.g., both E.E. and Cockney can have a glottal stop in butter, but Cockney has it more often? Or is it something else?

@TT,

I can’t speak for Wells, obviously, but I think this post on his blog last year suggests that he has developed some less-than-friendly views toward the notion of Estuary as some kind of clearly separate entity from other types of Southeastern English. And rightly so: it’s a fairly unscientific concept that has produced countless ridiculous semantic discussions. He also endorses the work of Joanna Przedlacka, who has shown that the original dividing markers between EE and Cockney are very arbitrary in the context of Southeastern English.

BTW, don’t mean to suggest word-internal t-glottaling is part of modern RP (except perhaps in some very informal context).

Okay. But I have to say I’m still unclear on the distinction between E.E. and Cockney. Just when I think I understand it, I’ll see someone who I always thought was a Cockney speaker get labeled as an Estuary speaker or vice versa. I’m just saying it’s really hard for an American like me to understand this distinction.

Actually, TT, it’s really hard for many phoneticists to understand the distinction! The JC Wells paper I linked to in the original post gives a good outline of earlier notions of the difference between Cockney and Estuary:

–Cockney can have t-glottaling word-internally in between vowels (“batted”) while Estuary apparently can’t

–Cockney has th-fronting (i.e. “mouth” –> “mouf”)

–Unlike Cockney, Estuary appears to have no h-dropping (i.e. “hand” –> “‘and”)

But, as Wells expresses in the blog post I just linked to, these are really just words. One person might have th-fronting, but not much t-glottaling. Another person might have few overt Cockneyisms, but some occasional word-internal t-glottaling. You can’t really put easy labels on these people. Estuary works as a term for accents that lie within the spectrum between RP and Cockney. But the specific dividing line between the two will always remain extremely vague.

yes, but ‘get off’ and ‘lot of’ you have mentioned exemplify the rule of ‘final t-glottaling’, not intervocalic glottaling.

I would say they’re both final and intervocalic. There may be some speakers who have t-glottaling in final positions, but only before a consonant or a pause, but they wouldn’t have it in lot of, etc.

well re this discussion, “butter” can (though only can) be glottalised in almost all northern dialects, a process that can’t have started much later than 1970. If we accept that “butter” doesn’t glottalise in estuary, then summat else must be going on than estuary interference with northern dialects.

If you go back to the Survey of English Dialects, intervolic t-glottalisation was found at Wibsey (outskirts of Bradford). That might’ve been a regional centre for its spread.

That’s really intersting Ed, you might be right. Though I suspect a wider start, perhaps in a particular industry… mining or weaving for example. The SoD’s tendency to go for the most conservative speakers might have missed this innovation.

It’s interesting that south and east Bradford is also the place where d > t is traditionally considered to be strongest.

Pingback: Link love: language (31) « Sentence first

Pingback: This Week’s Language Blog Roundup | Wordnik